How They Killed The Picket Line

8 July 2024

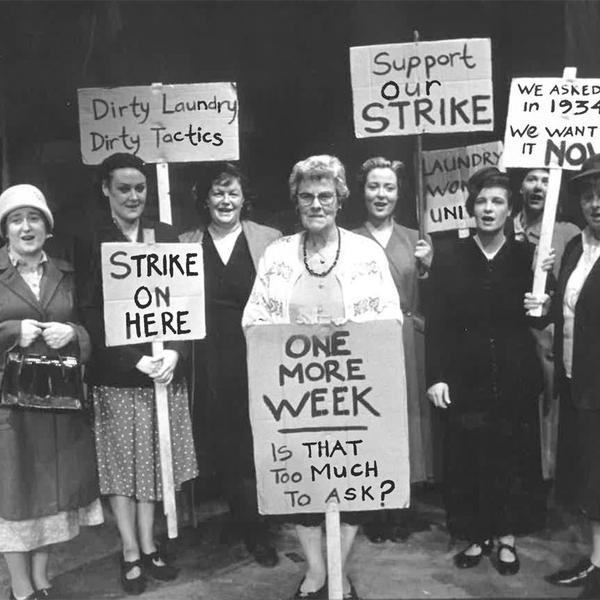

They used to be afraid of us – the bosses, the government – even our own union leaders were afraid of the militancy of grassroots workers in Ireland.

The bosses and union leaders all agreed – there was an “unnatural” respect for the picket line among workers in Ireland. A delegate from the Workers Union of Ireland put it this way at a union conference in the late 1960s:

“The problem concerning pickets is not that members would know which picket to pass and which not to pass. The problem is members will not pass any picket irrespective of whether it is official or otherwise.”

Union leader Denis Larkin explained the exceptional militancy of Irish workers to a late 1960s meeting of Congress, moaning in the same vein:

“You don’t have the same system in Britain, with all the thousands and thousands of militant trade unionists; you don’t have a situation as soon as a single individual decides that he’s going to have a strike – takes a piece of stick and puts a paper on it, and walks in front of an industry and everybody stops. That doesn’t happen in Britain, that doesn’t happen on the Continent, it doesn’t happen in the North of Ireland. It happens here because we have a particular commitment to being militant in that regard.”

A wave of militant strikes had the bosses, the government and union leaders scrambling about trying to think of ways to destroy the confidence of rank-and-file workers. Without cooperation between all those forces they wouldn’t have been able to cage the working class.

It took them years to tie us up, co-opt our unions and repress any militants. If we want to undo the damage that’s been done and recover our fighting spirit, we need to retrace our steps and look at how we ended up with Industrial Relations legislation that ties us hand and foot.

We must defy the Industrial Relations Act if workers want decent wages and any kind of standard of living at all. As teacher and trade union activist Eddie Conlon wrote after the Debenhams strike:

“The key issue in the strike became how to respond to injunctions and the threats of arrest arising from them. This feeds into a wider debate about how to respond to the Industrial Relations Act. The likes of the Communist Party, which has influence within Mandate, did not support a strategy of defying the injunction. They remained committed to a legalistic strategy of seeking to change the law and indeed argued against calling on other workers to take action to support the Debenhams workers as it would be illegal.

“Debenhams workers, especially in Limerick, showed how to render the Act ineffective. With the aid of supporters, they defied the injunction and the Gardaí and stopped the stock being removed from the shop over a number of days. I was reminded of what a teacher said to Eric Blanc in his account of teachers strikes in US states where striking is illegal: “It doesn‘t matter if an action is illegal if you have enough people doing it”.”

When people say “Irish workers don’t fight” it’s far from the truth. There was a massive revolt of workers from 1918 to 1923 which included general strikes, railway strikes, the takeover of factories and even the worker takeover of Limerick for two months.

The Irish rich came out on top of the War of Independence and adopted British laws wholesale – they intended to build a state machine, a mirror image of the British state, that would keep workers down and prevent a repeat of the revolutionary years.

The Irish slum landlords, factory owners and big farmers who controlled the political elite beat us back into submission using repressive laws, a corrupt police force and the Church. From the counter revolutionary years to the 1950s Ireland was a tough place for all workers, especially if they were in any way left wing.

Radicals were chased out of the country. While the bosses could call on the state to police the factories, the Church policed our minds. The poet Patrick Kavanagh said living in Ireland in the 50s was like “living at a wake” – no one disturbed the mourners’ thoughts. We were in mourning for a lost revolution.

The 1960s was a period of economic and social change in Ireland. A growing economy had led to near full employment and growing confidence among workers. Economic and political change led to a relaxation of some of the systems of control.

An influx of corporate investment made it necessary to introduce free education for workers and to soften the censorship and control of thought that had typified the 1920s to 1950s.

Books were taken off banned lists, but the ruling class were careful not to relax their control too much. Workers were ready to push for more. There were significant militant strikes in the 1960s that changed the face of industrial relations in this country.

The bosses had kept the lid on for so long that all the frustration that had been growing among workers suddenly came to the fore. With economic and political change in the air in Ireland, but also across the world, the stage was set for conflict.

By the end of the decade union boss Charles McCarthy was terrified that there’d be an uprising of workers – like the May 1968 student and worker uprising in Paris, France. “There were times we feared for the fabric of our society!” he said. The union leaders were more afraid of working class advances than the bosses were.

He was exaggerating the militancy of the rank and file to justify putting limitations on grassroots democracy in the unions – but it’s still clear workers were fighting back in massive numbers and with impressive militancy. In 1970 alone over a million days were lost due to strikes.

The 1960s kicked off with strikes at ESB, RTE, Bord Na Mona, Potez in Galway and dramatically with the bus workers. The state transport firm CIE regarded the bus workers as their most militant employees. The workers felt their wages were falling behind.

Most bus workers were in the ITGWU – 2,000 in Dublin alone. The smaller Workers Union of Ireland had about 600 workers. The management, headed up by Dr. C.S. Andrews, wanted to make CIE “pay its way” – as usual this was code for squeezing more out of workers and adopting private sector methods.

The issue that kicked off the strike was the introduction of one-man buses. There used to be a driver and a conductor on every bus. That was set to change. As usual the company lied by claiming the new way of operating would be only on some “provincial services” – but workers knew it was the company’s aim to generalise it.

When the boss tells you he’s only cutting off a finger, get ready to lose your arm.

CIE got impatient with delays and introduced the one-man buses on May 2nd 1962. They did it on purpose – they wanted to provoke a confrontation with the workers and then use the crisis to negotiate what they wanted. They wanted a scrap – and they got one.

The union leaders had already indicated willingness to not interfere in “management” issues at CIE. They didn’t oppose the one-man buses, only asking for transfer of the workers who were removed from the buses. Management was relying on compliant union leaders and their panic at the prospect of a strike. The bosses miscalculated when it came to the grassroots.

When 6 workers in Broadstone refused to go out without their conductors the company sacked them straight away. 2,000 angry bus workers gathered after midnight at the Theatre Royal in Dublin to decide what to do next. The meeting was called late to make sure the night shift could attend. The rank and file were furious with the company and demanded immediate action.

The union leaders tried to pour cold water on the fire and called for giving 7 days notice to the company and asking for negotiations. The grassroots and their union leaders couldn’t see eye to eye. The rank and file refused to leave their mates out in the cold. They decided to go out anyway and an unofficial strike started the next day.

The strike started on a Tuesday and on Wednesday morning the workers marched on the headquarters of the ITGWU demanding action from their own union. The union responded by taking disciplinary action against its own members and singled out the organisers of the march. The strike was being undermined by the leaders of the main bus union.

A meeting was called in the National Stadium by union leader Paddy Dooley – they were trying to secure a return-to-work vote. But workers were having none of it. The meeting ended in chaos and confusion as workers chanted and sang in unison: “Hang your head Tom Dooley, hang your head!”

The establishment in Dublin was panicking and got two Catholic priests to mediate between the strikers and the union. The union won the vote to return to work, but things didn’t end there. The union negotiated for the dismissed men to be reinstated but in return accepted the principle of one-man buses.

Many of the rank and file were angry because they believed the union had negotiated for reinstatement and not on the one-man bus issue. The workers rejected the deal in a vote but were asked to vote again, with the company claiming that one-man buses would only be introduced on day tours and private hire. The bastards lied.

When CIE tried to extend one-man operations in April 1963 there was such anger that the union was forced to call an official strike which lasted for 5 weeks. The newspapers of the time reported one the anger of grassroots bus workers:

“The lock-out strike which is to begin tomorrow morning has some of the ingredients of the 1913 strike and some of its penetrating bitterness. Anyone who meets busmen these days cannot but be deeply impressed by the passion and determination being shown even by the middle-aged and grey-haired men in this dispute. There is a bitterness abroad such as Dublin has not seen for fifty years.” Irish Times April 1st 1963.

The government intervened and demanded the unions sort it out. A new deal was cobbled together, put to the ballot and accepted. The union gave ground on one-man buses in return for sick pay and pension changes. “A spoonful of sugar makes the medicine go down” as Mary Poppins would say.

But concessions to management just led to more concessions. Once you give ground they wait a while and then come back for more.

There were rank and file objections to how the union had conducted the ballot. It was hard for the workers to stand up to the bosses when their own union was trying its best to stop action. Grassroots trade unionists were banned from holding office in their unions for five years to punish them for leading the initial unofficial strike and protest march. This was their “reward” for showing solidarity to sacked workmates.

It’s no surprise that hundreds of workers defected to other unions. In 1963 a grassroots group in Clontarf garage set themselves up as the Dublin City Busmen’s Union, followed in 1964 by workers from Dublin, Cork and Limerick forming the National Busmen’s Union.

Management commissioned a report into the dispute, which blamed the workers for being selfish claiming that “class consciousness is changing into self-consciousness” In fact the workers were displaying fantastic class consciousness by standing up for dismissed workmates, for organising grassroots marches and for challenging the company and their timid union leaders.

A National Industrial Economic Council was set up in 1963 and incorporated the union leaders into some level of embryonic partnership with the government. They were chuffed to sit at the table with the big boys.

Strikes in 1961 and 1962 had won workers wage increases and some workers had won more than others. The workers who felt left behind wanted to take to the stage. In talks with the unions the bosses offered a pay rise of 8% or 9% while Congress asked for 14%.

The employers’ representative bodies dug their heels in and stated they would never go higher than 10%. Fianna Fáil’s Sean Lemass got both sides to sit down and agree to a 12% rise on the condition that there’d be industrial peace. The papers were quick to call it the “Lemass 12%!” – heaping praise on the Fianna Fáil leader.

But it was the threat of strikes that had the bosses willing to compromise in the first place, not the “genius” of Lemass. Within a few short months of the deal inflation price rises had stolen the pay increase and workers were back to square one. Things heated up again.

The government spoke about strengthening the Labour Court to contain strikes and tie workers up in legal procedures. The union leaders agreed at a Labour/Employer conference that where both parties agreed to go to the Labour Court, there’d be no strike action and that one weeks notice would be given in cases where strikes were going ahead.

By August 1964 building workers had waited long enough – they acted. In October 1963 the question of the 40-hour week had come up. The Labour Court ruled that decreasing the hours of building workers to 40 hours would in effect be a pay increase beyond the agreed 12%.

Workers knew their wages weren’t keeping up with price increases and the 12% had been eroded already. A grassroots meeting of plasterers in Dublin decided that if the demand for a 40-hour week wasn’t met they wouldn’t come back to work after the August holidays.

Congress called an emergency meeting in the National Ballroom to try and prevent this action. The plasterers, the United House and Ship Painters and the Building Workers Trade Union called a strike which lasted months anyway – it lasted from August 19th to October 14th.

Unions that hadn’t supported the action agreed not to pass the pickets. 12,000 workers were able to shut down the whole building industry in Dublin. They used mobile pickets to extend the effectiveness of the strike – much to the fury of union leaders.

As the strike dragged on, unions began to argue and blame each other for the strike. But while union leaders in the striking unions were reluctant to strike, they’d been carried along by the groundswell of rank-and-file feeling.

Maurice Dobbin, the head of the building bosses, refused to give in. He banked on the support of Fianna Fáil’s Lemass because the government party was close to the builders. The brown envelope brigade was well represented among the building bosses.

There was a Labour Court meeting in September – but the building providers locked workers out on the day of the hearing. This brazen move just escalated tensions. Dockers in the Marine, Port and General Workers Union blocked all building supplies at the Port of Dublin in solidarity with their members who’d been locked out by the providers.

In September the plan was to extend the strike to cover Dublin Corporation, Dublin County Council, the Dublin Port and Docks Board, the Dublin Health Authority, CIE and ESB. The Congress leaders managed to block the strike on ESB, notice of which had been served by the Irish National Painters and Decorators union.

Grassroots anger was lighting fires and the union heads were busy trying to stamp them out. But an escalation of the strike could bring the bosses to heel. The union movement was divided. The government intervened and talks were set up at the Labour Court.

Bosses were forced to concede shorter working hours for the winter months and a commission was set up to decide on summer hours – in December 1964 it decided to lower those hours too. The 40-hour eek was won by some of the most militant strike action the country had ever seen – thousands of workers out, mobile pickets and threats to shut down massive public sector employers.

They’d even threatened to shut down ESB. The craft unions would later boast: “We got the 40-hour week, and we got it for everybody!” We take the 40-hour week for granted. But our class fought hard to win it. It wasn’t handed down from on high.

The government and employers desperately wanted to stabilise the situation and prevent a repeat of the strike wave. They set up a Joint Industrial Council for the building industry in May 1965 and set up new procedures to try to prevent disputes.

As newspapers carried news of the strike wave, they themselves were hit by a strike of print workers. Congress leaders were terrified of what they called a “free for all” on wages. Further talks with the employers collapsed and Congress decided to set a cap on pay demands. The unions were holding demands back.

They used low-paid workers as an excuse to limit other workers – they called for “solidarity” with the low paid. But if the better organised workers limited their claims the boss would never give the money they saved to a low-paid worker. It made no sense. It was just an excuse to try to curb the strike wave.

Taoiseach Sean Lemass decided the best course was to strengthen the Labour Court, giving it the power to make binding decisions. Even Congress knew this was a step too far and would destroy them, so they opposed it. This came at the same time as the government was introducing new anti-worker bills, taking moves to ban strikes in ESB.

The ESB workers were some of the most militant workers in the 1960s. As the Fogarty Report said: “Whereas in 30 years of the ESB’s existence down to the end of the fifties it experienced only eight strikes…from 1961 to December 1968 there were 38 trikes.”

Salaried employees at ESB decided to strike. The unions told manual workers to cross the pickets – which created massive anger. The strike was far too timid and lasted only a week. But wage differences between skilled workers, such as electricians, and the white-collar employees created a lot of resentment.

Electricians pay was set by “following the down-town rate” – this meant that their pay was tied to negotiations in wider private industry. The Electrical Trades Union (Ireland) had made a pay claim against both the private bosses and ESB in the Summer of 1961.

On August 21st pickets went up outside private companies and outside ESB. All the other ESB unions told their members to pass the picket line as the government took fright. Manual workers refused to listen to the union leaders and wouldn’t pass the picket lines. Respect for the picket was strong.

The Dáil and Senate were brought back for an emergency session to push through the repressive Electricity (Temporary Provision) Bill. This was to set up a state body that could force an agreement on both sides. The union leaders got scared and ended the strike.

Once the crisis had passed the idea of “compulsory arbitration” was removed by the government. It had worked as intended – the threat alone forced the union leaders to come crawling. The workers were offered 28 shillings a week – which was a massive amount at the time.

Manual workers pointed out that they’d respected the pickets and expected an increase too – they were granted the same as the electricians. Strikes worked. Other unions decided to punish manual workers who had gone out against their unions’ wishes by withholding their strike pay.

When ESB workers started joining the more militant of the ESB unions, the union was expelled by Congress. The bigger unions started losing members and so were forced to pay the strike pay due to members who’d taken part in strike action.

Clerical workers in ESB got a 12% increase from national negotiations and in 1965 got another 10%. All the other grades wanted to follow them and get the same increases. The government wanted to rationalise all public sector clerical pay but a consequence of this was a proposal for a pay rate below what ESB workers were getting.

This set the stage for another explosion of strike action.

Draughtsmen at ESB were in dispute in February 1966 as the government proposed disputes going to the Labour Court instead of to a tribunal. A rank-and-file organised “Electricians Association” declared their intention to strike but were persuaded to hold off by the Electrical Trades Union (Ireland).

The ESB fitters decided to act, their wages had fallen way behind the “down-town rate”. They demanded the same pay scale as the clerks. The fitters went out on strike. Pickets went up slowly but were eventually placed on all ESB operations.

The government moved to outlaw strikes by ESB workers in “some circumstances”. The fitters pulled their strike after they won a pay settlement but the new anti-worker legislation was still on the books, ready to be used against any ESB workers that dared to strike in the future.

While the unions called for repeal of the act, the government refused to budge. As the union leaders negotiated a new comprehensive deal, some of the lowest paid grassroots workers formed their own rank-and-file group called “The Dayworkers Association”.

This was an unofficial rank and file group. Growing frustrated with the talks, they stuck unofficial pickets on ESB. Congress leaders immediately disowned these workers saying:

“The unofficial action taken to bring about a strike in the ESB is in effect a repudiation of the unions who are engaged in negotiation.”

Even the government’s Fogarty Report said that the unions had left these workers waiting for so long that their frustrations were bound to erupt in action. The strike started on Tuesday March 26th. The government immediately dragged picketers before the courts under the new ESB legislation and issued massive fines.

The unofficial pickets shut down the whole industry. Workers respected the strikers. The union leaders were terrified this might lead to an explosion of solidarity strikes and were looking over their shoulders at the uprising and general strike that had just taken place in France.

ESB were really worried too, they paid the fines to the state. Official and unofficial union representatives all called for a return to work, which was accepted. The government commissioned the Fogarty Report- which many grassroots workers saw as a “whitewash”.

The report recommended amalgamation of unions to prevent smaller unions from instigating strike action. This would make rank and file workers easier to control. There were also some token criticisms of ESB management and calls for “peace pledges” – guarantees that workers wouldn’t strike.

Another unofficial group – “The Shift Workers Association” – were in dispute about the length of the working week. The official union movement ignored the claim. The grassroots group notified they’d go out on strike on April 12th 1972.

Congress issued a statement designed to isolate the workers:

“In the interests of the trade union movement and its members throughout the country who are suffering hardship and loss of employment as a result of the unofficial action of the members of the Shift Workers Association, the Irish Congress of Trade Unions calls on all workers in the employment of the ESB to cooperate in securing that the maximum possible amount of electricity is made available and full output resumed.”

Their statement could have been written by the employers or by the government. The unions decided to break the pickets and asked engineers to do the work of the shift workers. The shift workers were forced to return to work by the scab actions of the union leaders.

Workers at Bord naMona went out on strike too but it was the maintenance workers’ strike that really scared the bosses, the government and the union leaders. It was the most militant yet.

Maintenance workers were employed in every Irish industry – they kept machines running in both the private and public sector. In 1969 they were going to lead one of the most militant strikes since the Irish War of Independence. It was a very bitter dispute, union leaders even called counter pickets against the strikers.

Working hours of craftsmen on building sites had been reduced in 1964 and maintenance workers generally wanted to follow suit. The bosses and the Labour Court rejected the claim in 1965 and again in May 1966. A deal in October 1966 set a rate for maintenance workers across all industries and provided some flexibility regarding hours.

The bosses had pushed for the deal as part of a desire for more centralised bargaining with union heads that would curtail rank and file militancy. They’d rejected claims in 1965 and 1966 because they wanted an airtight agreement that would guarantee them industrial peace.

They expected that the union heads would be able to enforce such a deal over the heads of members of the unions. A national group of 18 craft unions was set up to sit down with the Federated Union of Employers.

When both sides sat down in September 1968 wages rates were a mess – the going rate for a 40-hour week was 7 shillings 9 pence an hour, but with many workers working reduced hours, the effective minimum was actually 8 shillings 3 pence. Some unions were asking for 11 shillings an hour, some for 10, some 15.

The old agreement was to end in December that year – just before the deadline the bosses made a derisory offer that infuriated the unions and especially angered rank and file workers. They’d watched their wages falling behind workers in industries whose machines they maintained.

The employers decided to take a strong stance to limit the wage increase. They decided to offer a £2 increase – the same as the government’s suggested increase in the last round of national pay talks. The unions just couldn’t go back to angry members with this and refused to attend a hearing in the Labour Court in January 1969.

The group of unions notified Congress that they were serving 7 days strike notice which was set to run out on the 24th of January 1969. Congress was angry with the unions as they wanted to follow the letter of the 1966 agreement which stated that strike notice wouldn’t be served until all other avenues had been exhausted.

But the leaders of the maintenance workers’ unions had the red-hot anger of grassroots members spurring them on to action. Congress was worried about pickets going up around the country and demanded to see a list of employers that were being targeted. The group of unions just replied they were targeting “members of the Federated Union of Employers”.

That kept it vague enough that the bosses in question couldn’t prepare for pickets and workers would catch them off guard – this would increase the impact of the strike.

Congress didn’t seem to understand that the whole point of the strike was to cause maximum disruption to the bosses so that they came crawling back to the negotiation table. Because of the nature of maintenance work the strike involved 193 different bosses.

Congress was panicking – they wrote a confidential letter to the striking unions begging for more time and argued that other workers would be affected by the strike. That was true but what happened to Larkin and Connolly’s idea of solidarity being a weapon workers could use to win?

The threat of a mass strike taking out workplace after workplace would have brought the bosses to the negotiating table begging for the strike to end. Thankfully the strike went ahead.

The strike started at the end of the workday on Friday January 24th and pickets went up at a few firms. Labour Court discussions went on until Saturday with no real result. Congress got some of the unions, the Amalgamated Union of Engineering workers (AUE) and the National Engineering and Electrical Trade Union (NEETU), to agree to lift pickets but not to end the strike.

But there was no mandate to lift the pickets despite the emergency meeting Congress had organised with employers. The bosses were shocked when pickets went back up within 30 minutes of the meeting – hitting big employers like Jacob’s biscuits. The chairman of Jacobs, Arthur Rice, was the head honcho of the boss’s representative body.

The news on the radio said the unions were asking for the pickets to be lifted, but members of the unions were already out on picket duty. It was too late to stop them! Hard-line bosses like Rice were furious.

After the weekend pickets hit 30 different companies. The unions couldn’t control the rank and file or even say which pickets were official and which weren’t. The negotiating group of unions fell apart and the bosses said they would refuse to negotiate with those continuing the strike action.

The bosses said they’d sack members of the striking unions – but this attitude just backfired. It encouraged more determined pickets.

900 rank-and-file union members met on February 2nd and confirmed the decision to keep the strike going. Congress called another meeting with all 18 unions representing maintenance workers to try and stop the picketing.

Despite this the strike escalated on February 5th. Congress begged the unions involved to suspend the strike for a month so they could negotiate with employers. They were losing control.

Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union workers in Limerick started a scab picket directed against the maintenance workers’ picket. Soon other unions started scab protests directed against the strikers. The strike faced the might of the bosses and the sabotage of union leaders who were urging counter protests.

Power passed to the rank-and-file elected strike committees, bypassing the union tops, as Con Murphy wrote in his official report on the strike:

“It appeared from evidence submitted that the authority of senior officers in the engineering and electrical unions was usurped by officials and persons of less responsibility and that the actual power did pass to the strike committee particularly towards the end of the dispute.”

The rank and file were taking control of the strike and escalating until victory. This was the right path to take to bring the bosses to heel. There were 30,000 workers out of work as more industries were shut down by the strikers. The union leaders tried to use this as moral leverage to get the strikers to quit. But a proposed deal in late February was rejected.

Cement Limited dismissed strikers, which just led to cement supplies being shut down in retaliation. The bosses were getting a slap every time they stepped out of line or played at being hard.

The employers mistakenly thought they were negotiating with the union leaders – but the strike had taught them a lesson. The fact that the strike was so militant and was led by a rank-and-file elected strike committee meant that nothing short of complete surrender by the bosses could end the strike. The bosses were slow to realise the predicament they were in.

By the end of February employers were getting demoralised. They knew they’d have to surrender. Individual companies started doing deals with some of the unions. One by one the dominoes started to fall. It was grassroots worker who had won this victory, despite counter protests by some of the unions.

The official report into the strike admitted it was grassroots leadership that had won the strike, setting “a dangerous process in industrial disputes in conferring de facto negotiating authority on a strike committee which it did not properly possess.”

If the government were against it, then the lesson was that more of that kind of grassroots control of disputes was needed. The workers became an unstoppable force.

A mass meeting of grassroots trade union members in the Metropolitan Hotel in Dublin was described by the press as: “Tempestuous, stormy, rowdy, noisy almost throughout.” That militancy was precisely what was needed to win the dispute. The bosses were terrified and by March 5th 15 companies had already surrendered and done a deal.

The Federated Union of Employers (FUE) begged the Taoiseach to do something to help them. But his hands were just as tied up as theirs. The workers weren’t taking any crap. The bosses decided to give in and agree to whatever settlement they could.

Hard-line boss Arthur Rice of Jacobs was furious and resigned from the FUE. But what else could he do but go off and sulk? He’d had manners put on him by the strikers.

The strike won a pay increase of 22% – a huge historic settlement – one of the largest amounts Irish capitalists were ever forced to concede to workers. Militancy had paid off big time. If the union leaders had had their way the bosses would have forced them to beg for an insulting offer. But the radicalism of the ordinary Irish worker had won this.

In the aftermath of the strike the government, the bosses and the union leaders needed scab legislation that would contain the rank and file and prevent explosions of militancy in the future. They all wanted to maintain the status quo and keep workers in their place.

The official government report argued that Congress should be given more power over unions and especially the rank-and-file members. They said there should be a “massive programme of trade union education and Congress should monitor major negotiations and have some early warning system.”

But early warning of what? That members wanted to fight and that fighting might actually bring the bosses to the negotiations begging for a settlement? The union leaders were acting like aristocrats of old complaining about the “ungentlemanly” methods used.

The bosses understood clearly that they needed to bring Congress on board and use them as a conservative force to police the working class movement. It was the bosses that were suggesting more power for the union bureaucrats to control the rank-and-file.

I remember a brickie telling me about a union leader who explained his hundred grand a year wage by saying “it puts me on the same level as the boss so he negotiates with me from a position of respect!” The maintenance workers challenged that cosy consensus at the top.

The unions and bosses sat down and agreed national wage settlements in 1970 and 1972 but undermining the power of the picket was foremost in the minds of those on both sides of that table.

The maintenance dispute led to a restructuring of the union movement. The government introduced the Trade Union Act of 1971 – this made it much harder to form a union and get a negotiating license. Potential unions would have to deposit £5,000, certify that they had over 500 members and then wait 18 months.

At a special meeting in Dun Laoghaire the unions too got down to undermining the picket – they brought in new regulations including differentiating between all-out strikes and “pickets to inform the public.” Where an all-out strike was required it could only be called by Congress and not by the affiliated union itself – after a heated debate this motion passed 173 to 123.

Mechanics at CIE were the first to test this new attitude to strikes – one union involved applied to Congress for permission to strike while another didn’t. Soon both unions were out but other unions instructed members to pass their pickets and the strike collapsed. Congress then threatened to expel the two unions who’d called the strike. So much for solidarity.

The bosses inserted a ‘peace clause’ into the National Agreements that the unions accepted without a word. The government, bosses and union leaders were all on the road to the repressive 1990 Industrial Relations Act – they just needed a significant dip in class struggle to force it through.

Strikes continued into the 1970s – 1977 was a really militant year. Workers continued to use militant tactics such as sit-ins to get their way. But it was also the year that Fianna Fáil were elected with an unprecedented majority vote.

The Labour party had benefited from the militancy of the 1960s – but they had no interest in leading a movement of rowdy workers and instead went into power with Fine Gael. They promised so much before they got in and then let workers down. The Labour/Fine Gael coalition was so bad the majority of workers voted Fianna Fáil.

Fianna Fáil had a massive mandate from voters. They were the first party of the Irish bosses but were able to bounce back into power on the back of the failings of Labour. The new government under gangster Charlie Haughey wanted wage restraint from workers.

Fianna Fáil had historically stolen Labour’s thunder by winning working class voters with promises of economic advance and nationalist rhetoric. When Haughey came to power a union band was there to play “A Nation Once Again!” to celebrate.

Rank and file anger was so strong that even the union leaders mouthed off against the new National Wage Agreements. The wage agreements since 1970 had been designed to curb militancy but represented a cut in real incomes when inflation, tax and other factors were taken into account.

Employers were able to use an ‘inability to pay’ clause to get around paying increases that were due to workers. The bosses were given many legal loopholes. A tighter relationship between the government, bosses and union leaders had developed right throughout the decade of the 1970s.

There was the Employer-Labour conference, tripartite talks, a greater role for the Labour Court and bodies like the National Economic and Social Council. They were trying to suffocate workers under the weight of bureaucracy and red tape.

The militant maintenance workers strike and the impact of the economic crisis that began in 1972/1973 saw the bosses demanding a more ordered way of controlling workers. Fianna Fáil even threatened to impose wage curbs as a stick to force compliance from the unions – not that the leaders needed much convincing.

Legislation dealing with unions was first introduced in Ireland by the British Empire starting with the Combination Acts of 1800 which said that all unions were “criminal conspiracies” but rising strikes, protests and trade union organising meant the British ruling class had to change tack and repeal the Acts in 1824/25. Unions were still treated with suspicion by the courts.

The British Conspiracy and Protection of Property Act of 1875 replaced the charge of criminal conspiracy by allowing strikes if part of a trade dispute, but whenever a dispute ended up in the courts the class prejudices of the judges were on full display.

A railway strike at the Taff Vale Company in South Wales led to the “Taff Vale Judgment” of 1901 which saw a union ordered to pay the company over a million pounds in today’s money, for the financial impact of the strike on the employer. The judgement made strikes almost impossible because the state would transfer the economic hit from strike action from the employer to the workers involved.

Opposition to the Taff Vale judgment led to the drafting of a new Trade Disputes Act in 1906 which made peaceful pickets legal. This British 1906 Act stayed on the law books in Ireland until it was replaced by the Industrial Relations Act in 1990.

When the Free State was formed the wealthy politicians just took over all these British laws including those covering workers.

The strikes of the 1960s had the government propose a Trade Union Bill in 1965 – but as we saw the level of resistance was too high to force it through. The bosses argued that the 1906 Act was encouraging unofficial strikes. A Commission of Inquiry into industrial relations was set up, but the unions pulled out.

Despite massive working class mobilisations at the start of the 1980s (like the huge tax marches) by the mid-1980s union leaders were facing a falling level of strikes and Thatcher had taken on and beaten the unions across the water.

The Irish union leaders argued that it was time to “negotiate” with Charlie Haughey and that Fianna Fáil were going to “hold back” the worst excesses of Thatcherism being proposed by the rabidly right-wing Progressive Democrats.

But the government was just playing good cop, bad cop – Haughey would eventually introduce the very same policies of deregulation, privatisation and outsourcing. But he’d have the union leaders in his back pocket when he did it. In Britain a fight was put up, most dramatically by the miners, but here the union leaders willingly tied up their own hands and feet.

Partnership between the government and unions began in 1987 and would last for another 25 years. “Our trade union leadership is very responsible!” said Bertie Ahern as the repressive 1990 Act was being introduced to the Dáil. It’s shameful to receive such praise from a corrupt little gangster like Ahern.

The 1990 Industrial Relations Act, introduced by then Minister for Labour Bertie Ahern, saw Fianna Fáil place massive limitations on Irish trade unions. Fianna Fáil had returned to power in 1977 and set up a “Commission of Inquiry on Industrial Relations” but it took them a few years to sew up this arrangement with the union leaders.

The 1987 Programme for National Recovery stated that “The Minister for Labour will hold discussions with the Social Partners about changes in industrial relations”. When Bertie Ahern made industrial relations proposals in 1989 the union leaders sang his praises: “…if it worked properly, it would make a positive contribution to the development of good industrial relations in Ireland”.

With a few changes here and there this became the regressive 1990 Act. Later some union leaders would express regret for supporting the 1990 Act, but they were in discussions with Ahern and knew exactly what was being proposed. They just thought that the Act would control their grassroots members and they could get on with the business of stuffing their faces in the corridors of power.

The whole 1990 Act was written from the bosses’ perspective. It ruled out taking action over ‘individual’ grievances unless the worker making the complaint had spent months fighting through the Employment Appeals Tribunal. This meant that a worker sacked for union organising couldn’t be reinstated through solidarity strike action, as this action was now illegal.

The union leaders had abandoned the old union value that “an injury to one is an injury to all” – effectively outlawing solidarity. The 1990 Act also changed the nature of pickets.

If a worker was victimised for union organising or blacklisted by a boss, the union movement would not act. The individual would have to contact a Rights Commissioner or the Workplace Relations Commission – which could take months to make any decision.

Imagine the worker had been doing a union drive? They’d be out of work for months before any ruling and that’d give the bosses exactly what they wanted – the end of the union recruitment drive.

After a strike at Dunnes Stores one striker was singled out and sacked. They had no legal option but to go to a Rights Commissioner and wait. The Act also ruled out actions like the big tax marches of the late 1970s – where workers had taken to the streets in tens of thousands to change tax laws.

It was lawful for workers:

“…acting on their own behalf or on behalf of a trade union..to picket..a place where their employer works or carries on business”.

But it was now illegal to ask members of the same union to come out in solidarity at other workplaces or help maintain pickets at a small workplace like a shop where they didn’t have the numbers for round-the-clock pickets.

This meant that mass solidarity pickets were also illegal. The maintenance workers had used militant flying pickets to great effect. The Act outlawed such effective actions.

The British 1906 Act made no distinction between primary and secondary pickets, but the Fianna Fáil Act changed that. Section 11(2) permitted secondary picketing “…if, but only if, it is reasonable for those who are so attending to believe…that that employer has directly assisted their employer…for the purpose of frustrating the strike.”

This was a ban on secondary pickets because it was impossible for workers to legally prove that another employer had “frustrated” their strike and given “direct” assistance to their own employer. And if it went to court the judges would just side with the boss. The bosses can afford better lawyers.

The union leaders used this as an excuse to encourage workers to pass picket lines, eroding the age-old respect for pickets that had been ingrained in the Irish working class. The ICTU leaders said:

“The mere fact that employees of another company are passing the picket line in order to carry out work for the employer in dispute would not in itself leave that company open to secondary picketing.” So much for real pickets.

Thousands of workers who worked on contracts, for example in catering, suddenly found themselves banned from picketing their actual workplaces because it wasn’t the primary address of their employer.

Picketing the college or school where they cleaned or worked serving food would now be ‘secondary’ picketing and illegal. The legislation also defended scabs:

“…the trade, business or employment of some other person, or with the right of some other person to dispose of his capital or his labour as he wills”. A picket that stopped a scab was now illegal. But then what was the point of a picket line if you couldn’t stop scabs?

The maintenance workers had won a 22% pay rise through effective pickets. The bosses, government and union leaders were trying to arrange it so the weight of the state would come down on any group of workers that ever tried that again.

The picket was hollowed out and made a token show of protest while the real work happened in negotiations at the top. It was still possible for unions to organise a ballot to black goods from a workplace involved in a dispute. But they wouldn’t use it unless pressured by workers from below.

The Act also banned collective decision-making. Workers couldn’t gather in a mass meeting and vote for strike action with a show of hands:

“…the union shall not organise, participate in, sanction or support a strike or other industrial action without a secret ballot, entitlement to vote in which shall be accorded equally to all members whom it is reasonable at the time of the ballot for the union concerned to believe will be called upon to engage in the strike or other industrial action”.

This part of the Act was taken nearly word-for-word from Margaret Thatcher’s Tory anti-trade union legislation. This meant union leaders could rely on postal ballots for votes that were taken without all members being present and hearing the arguments for and against from their workmates.

The vote would have to take place without “interference” from anyone in the union movement – persuading a worker to vote for action could be construed as illegal “interference”.

Employers were given new powers to get injunctions against pickets and the government would mediate in disputes using the new Labour Relations Commission. The LRC could drag negotiations out and dissipate any action.

These rules were an attack on the very idea of union democracy because the state was interfering in the internal rules and running of unions. Unions should be free to set their own rules but the government had dictated the manner in which votes would take place in the unions.

Bosses could also challenge any ballot legally. Even in the event that a majority of workers voted to strike they could be overruled by the union leaders with full backing of the Act. it was now legal for unions to overturn the democratic decisions of their own members.

But the union leaders weren’t allowed to call a strike if the members voted against one – they could only reverse a decision when workers had decided to go out and fight.

Immunities under the Act only applied to official trade unions, not rank and file groups like those that drove forward many of the strikes of the 1960s. If a minority of workers went out on strike despite a ballot against it – they would lose all legal immunity.

Militant tactics like workplace occupations would not be protected under the Act. The bosses had an array of injunctions they could use to threaten workers with cops, arrest and costs. The High Court had the power to grant an injunction against sit-ins.

Injunctions are often used to delay action – the boss can get the pickets pulled and then tie the unions up in the courts. This kills the momentum of a strike and can be used to demoralise workers.

One judge spelled it out:

“It is in the nature of industrial action that it can be promoted effectively only when it is possible to strike while the iron is hot, once postponed it is unlikely to be revived.” The 1990 Act allowed unions to go ahead with a strike within the restrictions of the Act and promised they couldn’t be hit with “ex parte” injunctions.

“Ex parte” means without the knowledge of the parties involved – where the boss would surprise the union with an injunction. But a third party, outside the dispute, could still apply for the injunction on the boss’s behalf even if they were just claiming to be a member of the public “inconvenienced” by the strike.

The bosses could also apply for “interlocutory injunctions” – these are injunctions granted in the presence of both the boss and the union. They can get these if they have a “prima facie” case – which means “on the face of it” – if it’s “obvious” to the judge that the union has a case to answer. The union has to prove that it’s pursuing a trade dispute but the Act makes that harder than ever before.

The boss is allowed question everything including the details of the strike ballot and can even be granted an injunction anyway based on “the balance of convenience” – meaning that the judge can say that the injunction only “delays” the strike and so “in the balance” of things isn’t a big deal – so grants it. But they know that a strike once pulled is very hard to get going again.

The union leaders welcomed these rules around injunctions. Madness. It soon became obvious that the Act was an attack on the very idea of working class solidarity and strike action. Look at the Nolan case of 1993 where some drivers at a small haulage company joined SIPTU.

Two union members thought they’d been sacked after an argument with management. A majority vote for strike action followed and a picket went up in February 1993. The company applied for an injunction and for damages from the union. The judge granted the injunction questioning the ballot for strike action.

At the High Court a judge claimed there was no dispute and the ballot was not valid. Therefore, the union had no legal right to call the strike action. The judge said because the whole argument was about union recognition they had no right to go on strike!

The company was awarded £601,000 in damages against the union – a huge blow to the union movement and a way for the state to scare the union leaders into submission. Their pot of money could be taken by the state and handed over to the bosses.

The union leaders claimed they’d been lied to by the government and had assurances that the Act wouldn’t be applied in this authoritarian way. But promises from Fianna Fáil aren’t worth a penny and by 1997 a survey of union reps at branch level showed that 73% believed supporting the Act was a mistake.

But the 1990 Act was part and parcel of a whole legal framework that accompanied social partnership – the union leaders were being brought into the corridors of power and offered up the rank and file, tied hand and foot, as an offering in return for that power.

Why did ICTU sign up to these Thatcherite laws? Trade unionist Gregor Kerr explained:

“Fianna Fail had chosen the path of ‘social partnership’ to tame the unions. They decided not to follow Thatcher’s example of declaring war. Instead, through involving them in the ‘decision-making process’, they very cleverly got the ICTU leadership to agree to voluntarily disarm its membership. Union leaders were prepared to go to any lengths in order to maintain their supposed position of influence.”

In 1991 SIPTU placed ads in the 1991 issue of “Management” magazine – targeting CEOs and managers with the claim that “Resolving Conflict is our Business”. The union bureaucrats were as interested in keeping control as Fianna Fáil were.

The cooperation of the union leaders in their own defeat led to a drop in union membership as demoralisation spread throughout hollowed-out and bureaucratic unions. Union density stood at 45.8% in 1994 but by 2003 this rate had fallen to less than 38% and continued to decline to under 28% by 2014.

By 2018 the number of trade union members had fallen to just 24%. The Act’s ban on political strikes made the anti-Apartheid action of brave 1980s Dunnes workers illegal, or the great tax marches of the late 1970s.

It was a great excuse for the bigger unions to abstain from the fight against austerity – like the mass movement against water charges. But it can be resisted. It will just take numbers. Look at how the Debenhams picket in Limerick was able to block the street and defy the cops and the 1990 Act.

Laws can be broken if you have numbers doing it. Look how we broke the law by refusing to pay water bills? But to get there we will have to build a grassroots movement within our unions. One that understands that we have to take on not only the government but our own union leaders too. We need to be more like the maintenance workers of the late 1960s.

(From our book “The Return of Class War Trade Unionism” available in the bookstore on this site)

RED NETWORK

RED NETWORK