The Trouble With Trotskyism

23 December 2025

It’s time to leave Trotskyism in the dustbin of history. To many this will seem like a left bubble debate but all the main forces on the Irish socialist left come from the Trotskyist tradition. If you want to understand the Irish left you can’t ignore Trotskyism. The Socialist Workers’ Network runs People Before Profit and is a sister organisation to the British Socialist Workers’ Party, part of the International Socialist Tendency. The Socialist Party and the so-called Revolutionary Communists both emerged from the Militant tendency, another British Trotskyist movement that spent many years inside the British Labour Party.

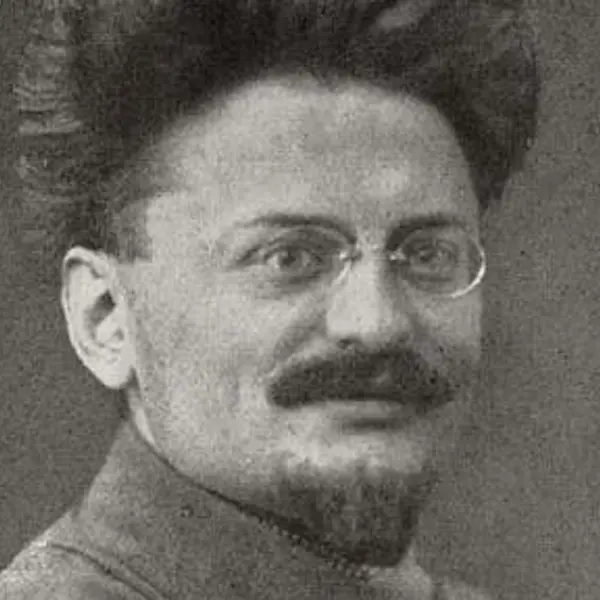

I want to argue that Trotskyism is the left wing of the middle class left. It’s not a working class ideology. Its job is to unconsciously sabotage the working class movement. It’s as far as you can travel towards real working class Marxism while still standing in the shoes of the middle class. That’s not to say that Leon Trotsky didn’t occasionally say interesting or worthwhile things and there’s no point denying the role he played as president of the St. Petersburg Soviet in 1905 and again in 1917, the leading role he played in the 1917 October Revolution or in the building of the revolutionary Red Army. Everyone should read his “History of the Russian Revolution”. But many of his political flaws continue today in many of his supporters.

There are many good individual Trotskyist activists. They mostly join whatever organisation they encounter first and then adopt its politics wholesale. Even the best of those individuals, as this article will explain, damage the left whether they know they’re doing it or not. We need a return to the actual revolutionary working class politics of the Bolsheviks - a return to fighting to build a working class party that while embedded in the wider struggles of our class holds onto principled politics. Trotskyism involves a distortion and falsification of Lenin. I don’t intend to do a comprehensive overview of Trotsky’s entire output but will highlight those aspects of his approach that still inform the modern Trotskyist left.

Let’s start with some of the political weaknesses inherent in Leon Trotsky himself. Like most Russian activists who came into activity in the years of rising struggle in the 1890s he helped to build workers’ unions. He helped build the South Russian Workers’ Union. He was initially attracted to Lenin’s principled “Iskra” group, who were known as the most orthodox and most revolutionary of Russian Marxists. Lenin was fighting for all the separate circles and factions that had grown out of the rising strike movement to unite into one socialist party with a clear revolutionary programme.

At the Second Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, the first real meeting of all these separate circles, the new party split into two main factions: the revolutionary Bolsheviks and the reformist Mensheviks. Leon Trotsky went into the room promising to defend Lenin but dropped his principles over the hurt feelings of some older famous intellectuals. The Mensheviks refused to subordinate these famous intellectuals to collective party democracy. Trotsky left the meeting in the opportunist Menshevik camp. “The Congress,” said Trotsky “has neither the moral nor the political right to refashion the editorial board. It is too delicate a question”. A party conference can’t vote to remove intellectuals from a leading body because it would hurt their feelings? It’s “too delicate a question” to ask each candidate to show their work and outline their political line? Lenin later explained the stakes:

“The issue thus came down to this: circles or a party? Were the rights of delegates to be restricted at the Congress in the name of the imaginary rights or rules of the various bodies and circles, or were all lower bodies and old groups to be completely, and not nominally but actually, disbanded in face of the Congress, pending the creation of genuinely Party official institutions?”

The intellectuals weren’t willing to subordinate their egos to the collective democracy of a united party. They wanted to keep their separate circles. They called Lenin “Robespierre” (the French revolutionary) and said he was a “dictator” because he argued they should respect the collective democracy of the party. The future Menshevik leader Julius Martov suggested a formulation of party membership that was so broad any worker could have claimed to be a member - but this would have created such a loose party that there would be no discipline. Formally it sounded like a “broad” membership base was better, in fact it would have allowed indiscipline to reign supreme. How could any revolution coordinate mass struggles against a state as monstrous as the Tsarist dictatorship without a cohesive organisation leading those struggles?

Lenin understood that while it sounded like a pro-worker formulation Martov’s idea of a broad party was actually about helping the intellectuals stay in their small circles and disrupt working class discipline: “In words, Martov’s formulation defends the interests of the broad strata of the proletariat, but in fact it serves the interests of the bourgeois intellectuals, who fight shy of proletarian discipline and organisation.” Lenin’s idea was for a tight organisation of revolutionaries who were organically embedded in wider struggle, lending the wider struggle organizational cohesion and revolutionary political guidance.

After the split the Mensheviks counterposed Lenin’s politics to the “self-training of the proletariat” in struggle. This sounded very bottom up and is repeated to this day by many Trotskyist groups, particularly People Before Profit. Lenin saw through it, it was a con job: “The proletariat will do nothing to have the worthy professors and high-school students who do not want to join an organisation recognised as Party members merely because they work under the control of an organisation. The proletariat is trained for organisation by its whole life, far more radically than many an intellectual prig. Having gained some understanding of our programme and our tactics, the proletariat will not start justifying backwardness in organisation by arguing that the form is less important than the content. It is not the proletariat, but certain intellectuals in our Party who lack self-training in the spirit of organisation and discipline, in the spirit of hostility and contempt for anarchistic talk.”

The whole concept of “self-training of the proletariat” was a way for the intellectual wing of the movement to claim to workers that the workers didn’t need clear politics and a disciplined party of their own. According to the Mensheviks a loose party thrown into struggle after struggle was supposed to automatically produce worker leaders, in fact it disarmed them. Lenin understood this would not be the case and that without an organisation of worker leaders the working class would remain subordinate to the liberal opposition to the Tsar. Lenin understood the secret: the middle class within the Marxist left was disarming the workers for the middle class outside the working class left to then take over and actually lead the movement.

The whole “self-training of the proletariat” line saw the Mensheviks reach back into the poverty stricken theories of what was called “Economism” - a reformist trend that many of the Menshevik leaders had previously joined Lenin in criticising. Lenin had written his famous booklet “What Is To Be Done?” against Economism, arguing against the idea that merely organising unions or going on strike would by itself create worker leaders. But now the Mensheviks needed a stick to beat Lenin with and refused to discuss the real issues at hand. Lenin was personally slandered, the real debate (about party discipline and democracy) was hidden behind a fog of gross misrepresentation. Leon Trotsky was chosen by the Mensheviks to attack Lenin in a pamphlet.

Trotsky wrote: “The year which has just passed has been a year which has weighed heavily in the life of our Party… But the basic task… may in general be formulated as consisting of the development of the self-activity of the proletariat.” Trotsky argued that the: “watchword ‘self-activity of the proletariat’ became a living and, let us hope, life-giving slogan.” Trotsky also argued that subordination to party democracy would lead to dictatorship: “In the internal politics of the Party these methods lead, as we shall see below, to the Party organisation “substituting” itself for the Party, the Central Committee substituting itself for the Party organisation, and finally the dictator substituting himself for the Central Committee.”

The irony was that Trotsky and the Menshevik leader Martov had had no problem with Lenin’s “What Is To Be Done?” for a whole year before the conference split! They did an about turn and found new “principles” so they could contrast their trend to Lenin’s. It was only after the conference they went looking for any argument that could be used against Lenin in order to defend their pandering to intellectuals’ egos and hurt feelings. This was gross opportunism. The Mensheviks started a boycott and active sabotage of the new party and older intellectuals like Georgi Plekhanov gave in and let them onto the central bodies without any vote by members, leading to Lenin’s resignation in protest at these undemocratic maneuvers.

Trotsky wrote on behalf of the Russian revolutionary intelligentsia, expressing their desire to continue leading the workers: “According to Lenin’s new philosophy… the proletariat only needs to have been through the “schooling of the factory” in order to give the intelligentsia… lessons in political discipline!… not the “school of the factory” but the school of political life, in which the Russian proletariat penetrates only under the leadership – good or bad – of the social democratic intelligentsia.”

Trotsky spent the next few years shifting back and forth between the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks, often criticising both. But when there’s a tug of war and someone stands in the middle pulling both ways, they’re not helping the revolutionary cause. He tried to bring all the factions who opposed the Bolsheviks together into an eclectic alliance which soon fell apart. ”Trotsky groups all the enemies of Marxism” wrote Lenin. When Lenin later criticised Menshevik deputies elected to the Tsarist Duma (a parliament), Trotsky condemned Lenin and said that Lenin’s criticism of the party’s parliamentary work threatened a split, Lenin replied: “Is it not monstrous to see something offensive in a calm acknowledgement of mistakes… Does this not show the sickness in our Party?” Lenin’s attitude was that the workers should be in on every debate.

Lenin also attacked Trotsky’s newspaper “Pravda” for spreading damaging ideas among the workers. An editorial termed the Bolshevik call for a republic a “bare slogan of the select few” and instead suggested they “teach the masses to realise from experience the need for freedom of association.” Experience would automatically train the workers to realise they needed legal unions? What would that do for the revolution? Lenin pulled out “What Is To Be Done?” once again writing: “This is the old song of Russian opportunism, the opportunism long ago preached to death by the Economists. The experience of the masses is that the ministers are closing down their unions… police officers are daily perpetrating deeds of violence against them - this is the real experience of the masses.”

In the 1905 Russian revolution Lenin and Trotsky had taken two different views on how the revolution would play out. Lenin’s position was that the coming revolution was a “bourgeois revolution” - that is a revolution that would end the feudal system, rule by the despotic Tsar and introduce capitalism. But Lenin never for one second trusted the Russian bourgeois class to actually revolt. They’d rather have kept the Tsar than have seen risen workers take power. That would have threatened their control over their factories. Lenin saw that the overthrow of the Tsar opened up the possibility of a fight for socialism. But Lenin was cautious with regard to how long the transition from one revolution to the next would take. It depended on the level of struggle internationally. But also on the attitude of the peasantry to the workers’ revolt. He avoided stagism (letting the bourgeoisie take the lead because it was supposed to be a bourgeois revolution) but also avoided ultra-leftism (ignoring the concrete specifics of the Russian situation).

Lenin’s position was to call for the “democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and peasantry” - “democratic” referred to the fact that it was a bourgeois revolution and “dictatorship” indicated that mass revolutionary bodies of workers and poor peasants would need to take power by force of arms. Russia was after all an overwhelmingly peasant country. So Lenin’s strategy was for the advanced workers, organised in a revolutionary party, to lead the working class who in turn would lead the poor peasants in an uprising. This uprising of the people would lead to, as Lenin noted: “civil war in full sweep - annihilation of Tsarism.” This would then lead to full scale war as internal and external enemies attacked the revolution - as Lenin wrote in 1905: “War: the fort keeps changing hands. Either the bourgeoisie overthrows the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat and peasantry or, this dictatorship sets Europe aflame. And then?”

The Mensheviks reasoned that because it was a bourgeois revolution that they should just tail the bourgeois liberals. This was the secret, unknown to even themselves, that saw them advocate for organisational and political models that disarmed the workers. The class instinct of the middle class was to prepare the ground for placing leadership in the hands of the bourgeois class. This abstract Marxism led them to the opposite side of the barricades when the 1917 revolution came. Leon Trotsky actually broke with the Mensheviks and took his famous position of “Permanent Revolution” - an adaptation of Karl Marx’s statements after the 1848 revolutions that the workers should not allow themselves “to be misled by the hypocritical phrases of the democratic petty bourgeoisie (middle class) into doubting for one minute the necessity of an independently organized party of the proletariat. Their battle-cry must be: The Permanent Revolution.”

The argument from many Trotskyists goes that Lenin simply adopted Trotsky’s position in April 1917. That’s just not true. Simply go and read what Lenin actually wrote. Lenin argued that the slogan “democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and peasantry” was obsolete in April 1917 because it had been achieved. Soviet assemblies, mass worker and peasant democratic circles, had arisen but because they were led by the Mensheviks they had refused to take power. This created a “dual power” situation where a bourgeois Provisional Government (the liberal and Menshevik path) sat side by side with the “democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and peasantry" (Lenin’s path).

Lenin wrote: “The situation that has arisen shows that the dictatorship of the proletariat and the peasantry is interlocked with the power of the bourgeoisie. An amazingly unique situation.” Trotsky, on the basis of his permanent revolution theory, said “No Tsar, but a workers’ government.” Lenin replied to this, writing: “This is wrong. A petty bourgeoisie exists, and it cannot be dismissed. But it is in two parts. The poorer of the two is with the working class.” So Lenin’s view was opposed to both Menshevik stagism and to abstract calls from Trotsky for a pure workers’ government. The Menshevik stagist position was later adopted by many so-called Marxist-Leninist parties and used as an excuse to ally with bourgeois forces. But Trotskyist groups argue to this day that they continue Lenin’s approach to the question, which is just not true. They continually falsify the actual debates of April 1917.

By the middle of 1917 Lenin’s Bolshevik Party had merged with the most militant Russian workers and everyone knew this. In the Summer of 1917 Trotsky and his small group joined them and he was elected to the Bolshevik Central Committee. He voted with Lenin for the October uprising and played a key role in the Civil War that followed the successful workers’ revolution. Trotsky took an abstract left position on the peace deal with Germany. While Lenin argued they should sign the deal as quickly as possible to halt the Germany military advance, Trotsky argued they should delay the negotiations in the hope of a future German revolution.

While the German revolution was a real possibility in the coming years it wasn’t an immediate prospect. Every day they delayed the Germans took more land. The Russians signed the treaty in March 1918 - the premature and failed German “Spartacus” uprising wouldn’t happen until almost a year later, in January 1919. To have delayed the treaty signing as Trotsky had suggested would have meant a months-long German advance and the possibility of the complete defeat of the Russian Revolution. Lenin wasn’t willing to risk the world’s first successful working class uprising on abstract reasoning.

Trotsky hadn’t had the experience of building a mass party full of rowdy workers and had a habit of ordering people around in an authoritarian way. This worked well during the Civil War but afterwards Trotsky argued fiercely with Lenin over issues like Trotsky’s suggestion to militarise all the Russian trade unions. Trotsky once again employed abstract logic - they had a workers’ state so why would the trade unions need freedom to organise? Lenin, as usual, had a concrete grasp of the complexities of their situation when he argued for the continued autonomy of the unions.

Lenin replied that their state was a workers’ and peasants state “with a bureaucratic twist”. They were in a backward country under war conditions and had necessarily had to re-employ countless Tsarist bureaucrats to their state machine. Not to mention the Red Army was full of former Tsarist officers. Lenin was acutely aware of the dangers of the situation and understood this required a nuanced view of the Russian Soviet state machine and that this meant defence of the workers’ right to form independent unions to defend themselves from the state bureaucracy. Lenin understood the workers needed to form a counter balance to the state. He understood the state as a concrete reality, not as an abstraction.

The Russian Revolution failed to spread. Germany had a failed minority uprising in 1919 followed by a crazy ultra-left attempt at an uprising in March 1921, followed by an aborted revolution in October 1923. The failure of the German revolution was the turning point for the Russian revolution too as they were isolated by imperialism. Any revolution that doesn’t advance begins to fossilise. Lenin died in 1924 and criticised all the leading Bolsheviks in his will. He wrote that Trotsky was “distinguished not only by his exceptional ability – personally, he is, to be sure, the most able man in the present Central Committee – but also by his too far-reaching self -confidence and a disposition to be far too much attracted by the purely administrative side of affairs.”

Lenin called for Stalin’s removal but he also noted that Trotsky’s ego and tendency to authoritarian command ran counter to his intelligence. During some of the faction fights after Lenin’s death Trotsky sat reading French novels and ignored the debates. He tuned out. Lenin would have never done that. Trotsky was exiled from Russia in 1929 and ended up in exile in Mexico where he tried to birth a movement in his own image. He was assassinated by a Communist agent who had pretended to be a supporter in August 1940. Even his children were murdered one by one at Stalin’s command. Trotsky wasn’t the only former comrade of Lenin’s murdered; most of the leading Bolsheviks of 1917 perished in the purges of the 1930s.

While Trotsky wrote some worthwhile works in the 1920s his isolation from the working class in his years of exile saw him return to his former Menshevism, this was clearly evident in his so-called “transitional demands” of the 1930s. His followers were small in number and didn’t have much authority among workers. This was the case in most countries outside the USA where there existed a moderately sized Trotskyist party. Isolation from the working class was a breeding ground for religious thinking and the formation of religious sects. Trotsky proposed a way for the tiny sects that followed him to skip over the long hard work of building up a layer of revolutionary workers by utilising his “transitional demands”.

Trotsky wrote in 1938: “It is necessary to help the masses in the process of daily struggle to find the bridge between present demands and the socialist programme of the revolution.” He continued: “This bridge should include a system of transitional demands, stemming from today’s conditions and from today’s consciousness of wide layers of the working class and unalterably leading to one final conclusion: the conquest of power by the proletariat.” The implication of the transitional demand method was that the demand itself would be enough, combined with the force of apocalyptic circumstances, to create a class conscious minority of workers. But what about the preparation of a class conscious minority of worker leaders which must happen long before you get to a moment of revolution?

Trotsky argued the revolutionary minority was to find demands that were compatible with the consciousness of “wide layers of the working class” but at the same time “unalterably” led to revolutionary conclusions. Demands that were compatible with “wide layers” of the working class were going to inevitably be reformist demands – as Karl Marx long before had pointed out:

“The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas, i.e. the class which is the ruling material force of society, is at the same time its ruling intellectual force. The class which has the means of material production at its disposal, has control at the same time over the means of mental production, so that thereby, generally speaking, the ideas of those who lack the means of mental production are subject to it.”

Calling for mobilising social movements on “reformist” demands – like when workers strike calling for higher wages, or the fight against water charges here in Ireland – is vital, abstention from such strikes and reform based movements divorces the militant minority from the mass of the working class. But the real problem lies with Trotsky’s suggestion that there is an automatic progression from reformist demand to revolutionary consciousness, for Trotsky said his transitional demands were those that were “unalterably leading to one final conclusion: the conquest of power by the proletariat”. He clearly used the term “unalterably” – once the demand was correct the progress to revolutionary consciousness was “unalterable”.

Trotsky said the transitional demands were necessary because of the “maturity of the objective revolutionary conditions” and the contrast between this and the “immaturity of the proletariat and its vanguard”. So he admitted that even the leading sections of the workers did not yet have a socialist consciousness and the transitional demand was supposed to build a bridge between this confused and fractured vanguard and the broad masses - who would necessarily stand on an even lower level of class consciousness. This was to be achieved by coming up with reformist demands that capitalism would not deliver. When the workers banged their heads against the system they’d magically all become revolutionaries. The demand was supposed to enlighten the minority and majority simultaneously, through activity. This was a return to the politics of Economism.

This was merely a repetition of the old Menshevik slogan of “self-activity of the proletariat” that Lenin mocked as far back as “What Is To Be Done?” Trotsky disarmed the advanced minority and made them not the bearers of revolutionary politics but the bearers of transitional, reformist, demands. Trotsky gave this “transitional method” to his international groupings of supporters – most of whom were tiny isolated sects composed of academics and students. They were given a religious text – told that with the correct reformist demands they could summon up armies of class conscious workers. This was reassuring when you were in a small group, but it was religious, false hope, all the same. The formalism inherent in this programmatic approach was perfect for middle class groupings who could believe that the right piece of paper would solve all material problems.

This led to a proliferation of Trotskyist sects who all claimed to have the correct demands often using the requirement of demands being acceptable to “broad masses” to offer nothing but reformism to workers – this gross formalism, whereby the material reality of a party like Labour in Britain, as a political expression of the union bureaucracy, faded into the background and the strategy for socialists became one of winning this party to the transitional demands. The demands could overcome any reality. If the bureaucracy signed a piece of paper with these demands on it the British state and the Labour Party running it would be magically transformed.

The misuse of the minimum maximum programme by reformist Social Democracy was rightly criticised by Trotsky – minimum demands were those made by revolutionaries under capitalism. Maximum demands were those we propose to undertake after a revolution. For Social Democracy the day to day minimum demands became the real programme of the party and the revolutionary maximum demands were farmed off to a future that no one really thought would ever come – and when it did come the German Social Democrats conspired with the state to murder revolutionaries like Rosa Luxemburg. But the problem with Trotsky’s critique of the minimum maximum method was that this was precisely the method of the revolutionary Bolsheviks who campaigned on their “three whales” - the minimum demands for an 8 hour day for workers, land for the peasants and a Russian constituent assembly. The Bolsheviks used campaigning on these “three whales” to call for a revolution. They never hid their maximum demands behind the minimum demands but used one to open a conversation about the other.

Trotsky admitted that his transitional programme did not remove the necessity of the old minimum programme saying: “The Fourth International does not discard the program of the old “minimal” demands to the degree to which these have preserved at least part of their vital forcefulness. Indefatigably, it defends the democratic rights and social conquests of the workers.”

He admitted that it was still necessary to engage with worker movements on minimum demands – to fight for higher wages or to defend the limited democratic rights workers had under capitalism. Therefore he said the old minimum demands still existed alongside the transitional demands. So he wanted a minimum programme, a halfway house transitional programme and, if you were not an opportunist, there was still the need to articulate a maximum programme! What a complete Menshevik mess!

Even after the October Revolution Lenin had insisted on keeping the minimum section of their programme in case they had to retreat. The programme was a totality that indicated, as the Communist Manifesto terms it, “the line of march”, it said: “we intend to start fighting here on these issues and end up here!”

An apocalyptic backdrop set the scene and allowed Trotsky to paint denied reforms as leading automatically to revolution. Today groups like People Before Profit will argue that while each of their policies are compatible with capitalism the totality isn’t and that social movements organised around those policy demands will one day simultaneously confront the system and automatically progress to revolution. This is abstract schematic nonsense. The reforms that were promised by the Greek radical left party Syriza before they took power didn’t lead to revolution when they were denied to Greek workers, instead there was demoralisation and the Greek equivalent of Fianna Fáil returned to power. Without a significant revolutionary minority, present in the working class before a reformist left government coalesces with capitalism, the result of denied reforms is demoralisation. Syriza actively used influence over the trade union bureaucracies to suffocate the movement. The result was confusion.

Let’s look at Leon Trotsky’s actual demands, he first proposed a “sliding scale of wages”. This was certainly popular among the masses but in a US economy booming during New Deal pre-war mobilisations, something that was not exactly unrealisable under capitalism. This was a moderate demand - that you could and should have mobilised workers on but it held no secret revolutionary power. Next he proposed “factory committees” – he said that these would lead to the establishment of workplace “soviets” - workers’ councils. Not a bad demand but realisation would depend on the specific circumstances of the country in question and full realisation – transforming factory committees into soviets would only take place in a revolution and at the call of revolutionaries. In countries with a long history of trade unions workers could be diverted from the need for their own factory based councils unless revolutionaries were already present in the unions arguing for a rank and file strategy that favoured grassroots workplace organisation.

Another transitional demand Trotsky wanted his followers to put out was the call for a “Workers and Farmers Government” – this was similar to current calls for a left government and suffered from some of the same confusions. Trotsky made some highly problematic formulations to justify this demand. He wrote: “If the Mensheviks (Russian reformists) and SRs (radical peasant party) had actually broken with the Kadets (bourgeois liberals) and with foreign imperialism then the workers and peasant’s government created by them could only have hastened and facilitated the dictatorship of the proletariat” This was absolute bullshit!

If the reformists in Russia hadn’t been reformists then the reformists wouldn’t have done what they, as reformists, did? This is just plain stupid. The parties of the Russian middle class, the petty bourgeois Mensheviks and SRs , tailed the party of the Russian bourgeois class, the Kadets, because of the gravitational pull of class interests. Asking the petty bourgeois to go against its own class nature was a belief in the supernatural. It smacked of desperation and was the point of view explicitly criticised by Lenin when he wrote: “the idea of a parliamentary road to revolution where “the majority of the people shall vote (with the voting supervised by the bourgeois apparatus of state power) “for revolution”! It is difficult to imagine the extent of the philistine stupidity displayed in these views… Only scoundrels and simpletons can think that the proletariat must first win a majority in elections carried out under the yoke of the bourgeoisie, under the yoke of wage slavery, and must then win power. This is the height of stupidity.”

Trotsky was also arguing that pressure from below could transform the Mensheviks and make them into revolutionaries. Movements from below can of course force reforms and concessions from any government left or right, but it does not transform this government or the capitalist state machinery it rests on into something else. “If the Mensheviks.. had broken with the Kadets” - but the petty bourgeois Mensheviks were never going to break with the bourgeois Kadets. A mouse can never turn into a lion because you apply external pressure. This was a belief in miracles. Trotsky’s authoritarian disposition made him a bad choice to build the Communist movement after Lenin’s death. But even more of a barrier was his flawed programmatic model.

Let’s look at the movement he birthed in an Irish framework. The largest Trotskyist group in Ireland is the Socialist Workers Network who run People Before Profit (PBP). They hide their politics under the PBP label but their philosophy can best be described as programmatic nihilism. The mantra in the SWN (and therefore PBP) is the Menshevik one that “struggle educates” and politics is secondary and functional, subordinated to the requirements of motivating the next mobilisation or merely expressing the immediate demands of social movements. National meetings are simply motivational cheerleading sessions to keep members in a state of moral panic about the next protest and anyone who expresses any kind of critical thinking is part of the “internalised left”.

They, of course, write articles about Lenin and various other radical topics but the approach is eclectic. They’ll have an SWN talk about Lenin’s “State & Revolution” while simultaneously putting out press releases as PBP that offer to enter government. Without a programme these eclectic parts never form a coherent whole and abstracting revolutionary politics from the everyday activity of PBP weakens both the SWN and PBP. The politics of the SWN becomes abstract and the politics of PBP softens.

The politics of the Socialist Workers Network has its origin in the British Socialist Workers Party, founded by Tony Cliff. The SWP started as the Socialist Review Group in 1950s Britain. They started with about 30 members, mostly intellectuals, recruited from the British Labour Party. They began as “Luxemburgists” explicitly rejecting Lenin’s concept of the revolutionary party and they wholeheartedly supported Leon Trotsky’s 1904 attack on Lenin. Their founder

Tony Cliff wrote: “Rosa Luxemburg’s conception of the structure of the revolutionary organisation – that they should be built from below up, on a consistently democratic basis – fits the needs of the workers’ movement in the advanced countries much more closely than Lenin’s conception of 1902 - 4, which was copied and given an added bureaucratic twist by Stalinists the world over.”

The Socialist Review Group became the International Socialism Group (IS) at the end of 1962. Later, Tony Cliff wrote a multi-volume biography of Lenin that often twisted Lenin’s politics to force Lenin to give voice to the political positions of his rivals in the Russian socialist movement. The SWP’s so-called turn to Lenin at the end of the 1960s was merely to accept “democratic centralism” as a mode of decision making. Democratic centralism means open and free debate and then unity in action. It was common to both the reformist Mensheviks and the revolutionary Bolsheviks in the Russian socialist movement. It wasn’t by any means the key to Lenin. If Menshevism was a petty bourgeois political philosophy surely it would take more than just the adoption of the form of decision making to escape Luxemburgism and transform the SWP into a Leninist organisation?

Tony Cliff made just one alteration to his book on Rosa Luxemburg to indicate this “profound” shift. The turn to Lenin in 1969 came after 19 years of promoting Luxemburgism as their organisational and political model. The SWP grew from the protests and strikes at the end of the 1960s but Cliff soon got tired of recruiting workers and with some shop stewards being pulled by the “Social Contract” of the incoming Labour Party, decided to take a shift towards anti-racist work and recruiting youth - indicating the SWP’s desire to go chase pools of easy recruits.

They always tailored their theory to fit the necessity of open door recruitment. During the Korean war in the 1950s their slogan was “Neither Washington Nor Moscow” - equating both sides despite the Korean war being an imperialist war. When the 1960s anti-war movement rose against the Vietnam War and there was the prospect of recruiting lots of radical students the SWP changed tack and focused on the USA as the bad guys, instead of objecting equally to both sides. The objective reality of imperialism underlying both wars hadn’t changed. These were the same wars. What had changed was that in the 1950s the SWP tailored their arguments to recruit from pacifist CND and in the 1960s they tailored their arguments to recruit from the student anti-war movements. Pools of potential recruits often determine their political positions, not a study of objective reality.

They’d recruit people on the basis of cheerleading the current fad - and lose them just as quickly. In January 1977, the IS was renamed the Socialist Workers Party. By 1982, the SWP was refocused completely to a propagandist approach, with geographical branches as the main unit of the party, a focus on abstract Marxist theory and an abandonment of the perspective of building a union rank and file movement. They spent the 1980s huddled in local branches talking abstract Marxist politics - apart from the occasional intervention as during the Miners strike. They refused to use electoral work to leverage some small support in working class communities which could then have acted as the basis of a left recovery. Local branches shrunk and most leading members were academics and students.

They wasted a decade. They could have campaigned in working class estates, electing local councillors and prepared for a future upturn. Tony Cliff once infamously argued that tactics can contradict principles - Cliff’s Irish disciple Kieran Allen took this subordination to immediacy seriously and ran with it. This was a form of opportunism, but from below. The German reformist Eduard Bernstein had once written: “For me the movement is everything and the final goal of socialism is nothing”. The SWP echoed this opportunism from above but transformed it into opportunism from below. The final goal of socialism was for the SWN an abstraction, a Sunday school sermon to be related to members at internal meetings, but for the working class? No. They’d only get the politics of the movement, of the moment.

This political schizophrenia is inherent in their Menshevik style allergy to political programmes and adherence to the philosophy of automatic progression of class consciousness through struggle. The SWN in Ireland was formed in 1971 and after 54 years has about 150 activists North and South. They distinguish themselves on the left by arguing that they “don’t have all the answers!”, “we listen to the people!”

“Listening to workers” is of course a vital part of constructing your minimum, everyday demands. But even then there’s always the necessity of understanding the economic and political situation, rising above the moment and selecting demands on the basis of a future line of march. When it comes to social issues like racism and sexism the SWN wouldn’t just “listen” - they’d rightly filter out reactionary demands. That process of selection on the basis of Marxist politics, on the basis of theory, is key. But they don’t apply this approach to the state, to parties and social movements. Once you start to think about it, “we don’t have a programme, we listen!” is ideologically incoherent and intimately connected to the building of a disorganised, frenetic organisation.

Each branch of such an organisation is “listening” to different groups of workers and the consistent application of this philosophy leads to each area merely articulating its own interests, the interests of other parties that influence the branch, or at best the partial interests of some section of the working class.

That’s why the SWN is divided into competing factions, each blaming failings on individuals and refusing to find a programmatic reason for those failings. PBP was formed 20 years ago with the promise that it would harden up as struggles progressed. That never happened. As deceased socialist John Molyneux wrote: “It is not a united front. Perhaps it had some characteristics of a united front when it was first formed, but it certainly isn’t one now. A united front is an agreement between two or more different organisations and forces (parties, unions, campaigns, etc) to form a common front on a particular issue or cluster of issues such as combating fascism, fighting racism, defending workers jobs, defeating water charges, etc. PBP is clearly a political party that not only consistently contests elections but also has a comprehensive programme of policies.”

Academic Kieran Allen, a leading PBP thinker, during the United Left Alliance days attacked the very idea of a socialist programme, he wrote: “An ounce of struggle is worth a ton of political programmes. The ULA spent a lot of time discussing a ‘principled socialist programme’ and far less time in actually campaigning. An internalised atmosphere pervaded many of its gatherings because of this emphasis. The assumption was that if agreement could be reached on an extensive socialist programme, this would inoculate the ULA against any reformist deviations. In reality, a broad left party needs a fairly minimal programme.”

These are precisely the arguments the Mensheviks made against Lenin. But you can campaign, you can struggle and you can have principles at the same time. It’s not that difficult. What the SWN takes from Leon Trotsky is the Menshevik legacy of “self-training of the proletariat” - a philosophy which Lenin argued was an attempt to curtail the development of worker leaders and their uniting in a revolutionary party, a party that was embedded in all the struggles of the class but used authority won in the course of these struggles to openly call for a revolution. The programmatic nihilism of the SWN has seen them end up in the same place as the transitional programme advocates - they call for a left government that will break with capitalism. They argue that the demand for a left government is popular and should therefore be articulated and that when workers bang their heads against the system they’ll want to go further.

Our Red position on left government has always been clear: Sinn Féin will never break with capitalism, neither would Labour, the Greens or the Social Democrats. Our job is to say to workers that any Red TD would vote out Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael but to also say honestly that the government that replaces them will not challenge the capitalist system. We would remain outside such a government and support it case by case in order to advocate for the working class. Struggle can force concessions from such a government but cannot change its nature.

The Socialist Party (SP) and the smaller Revolutionary Communists of Ireland (RC) have their origins in the Militant Tendency in Britain. Paul Murphy TD’s “Rise”, a faction inside PBP, is a split from the Socialist Party. When Militant were kicked out of the British Labour Party in the early 1990s leading future RC theoreticians, Ted Grant and Alan Woods, considered that leaving Labour was an “ultra left” turn. They stayed in Labour calling themselves the “Committee For A Marxist International” and published a paper called “Socialist Appeal”. They were called the International Marxist Tendency for a while. They spent years mocking anyone that wasn’t in the Labour Party and yet when they were eventually expelled decided Labour had been capitalist all along. More magical thinking.

While the Militant Tendency renamed themselves “The Socialist Party” and gave birth to a sister organisation in Ireland of the same name, the Ted Grant faction renamed themselves the “International Marxist Tendency” in 2004. That meant that Grant’s supporters had been in the British Labour Party from the late 1950s until 2024. The “Revolutionary Communists” claim an unbroken thread connects them, through Ted Grant, back to Trotsky and Lenin. But Grant abandoned many of Lenin’s key ideas and twisted many others.

Being an active Labour Party member for decades deformed the politics of the Militant Tendency. Many of their flawed positions - on the state, the police, on imperialism - can be traced to pandering to the British union bureaucracies who ultimately control the Labour Party. Militant’s grotesque formalism can be traced from their time in Labour - believing that the Labour Party could be transformed into an instrument of revolution requires magical thinking, all assisted by the transitional method of Leon Trotsky.

For decades Ted Grant was the main theoretician for the Militant Tendency. He developed their justifications for working through the British Labour Party, as he wrote as far back as the 1950s: “To the sectarian splinter groups… the problem is posed in the simplest of terms: Social Democracy and Stalinism have betrayed the working class; therefore the independent party of the working class must immediately be built. They claim the independence of the revolutionary party as a principle, whether the party consists of two or two million.” This was his usual style - everyone outside of the Labour Party was a “splinter group”.

“The working class does not come to revolutionary conclusions easily. Habits of thought, traditions, the exceptional difficulties created by the transformation of the Socialist and Communist traditional organisations into obstacles on the road of the revolution; all these have put formidable obstacles in the way of creating a Marxist mass movement. All history demonstrates that, at the first stages of revolutionary upsurge, the masses turn to the mass organisations”

Their strategy was to join Labour or Communist Parties and build a Trotskyist faction inside, waiting for the day the masses inevitably returned “home” to those parties. They adopted a reformist view of the state and adapted to the pro-imperialist union bureaucracy. For Lenin the Labour Party was “capitalist workers party” - Grant rejected this view. Instead of being agents of the capitalist class in the working class they were expressions of the class. When Lenin recommended Communists in Britain join Labour it was to get the ear of leftward leaning workers and expose the leaders of the Labour Party as traitors. The Communists were to “help” Labour win elections only if the revolutionaries would say to the workers: “We must, first, help Henderson or Snowden (of Labour) to beat Lloyd George and Churchill… second, we must help the majority of the working class to be convinced by their own experience that we are right, i.e., that the Hendersons and Snowdens are absolutely good for nothing, that they are petty-bourgeois and treacherous by nature, and that their bankruptcy is inevitable; third, we must bring nearer the moment when, on the basis of the disappointment of most of the workers in the Hendersons, it will be possible, with serious chances of success, to overthrow the government.”

Lenin was for telling workers the truth, clearly outlining that the whole plan was to get Labour into government to show them up as “treacherous” and then the plan was to overthrow them! Lenin did not say to go around telling workers that Labour, armed with a socialist programme could just nationalize the commanding heights of the economy and that would be socialism! Lenin said: “I want to support Henderson (Labour) in the same way as the rope supports a hanged man!” The way a “rope supports a hanged man!” The point of Lenin’s tactics was to prepare workers to overthrow a left government and replace it with democratic mass assemblies of workers.

Ted Grant instead wrote things like this: “Should Labour win the next election, the bill will be presented by the workers accordingly. The advanced elements in the unions and LP will demand steps in the direction of socialism.” The conservative counter revolutionary bureaucratic bulwark of the British Trade Union Congress was going to demand steps in the direction of socialism? This was stupid. It was insane formalism to think a programme could transform the bureaucrats. Even if rank and file members put pressure on the bureaucracy, the bureaucracy itself would never change its petty bourgeois nature.

Grant repeated it over and over for decades and into the 1980s: “The one thing that blocks the way for a peaceful transformation of society in Britain is the attitude precisely of the Social Democrats and of their counterparts in the Solidarity group of Labour MPs. They do not wish to provoke the ruling class by suggesting a change in society… A new period opens up in which only the transformation of society will solve the problems of the working class. What is necessary is for a Labour government to operate on the policy which is advocated by Militant. Break the power of big business by taking over the major companies and organise production on the basis of a plan.”

Militant condemned “both sides” during the Falklands War: “The ultra-left sects of various descriptions have - quite predictably! - supported Argentina on the grounds that it is a colonial country faced with imperialist aggression. That is nonsense…On the Falkland Islands themselves… Had there been a colony of, say, 100,000 Argentines, a case for colonial oppression could have been made out. But the Islands have been in British possession for 150 years.”

Some socialists they were, giving left cover to Thatcher’s imperialist aims and condemning everyone else on the left for being “ultra-left sects!” Then they went on about the rights of the British inhabitants of the Falklands who were oppressed by Argentina. Never mind the full might of the British state was bearing down on the Argentinians. It is the duty of Marxists in any war to call for the overthrow of their own government. The main enemy is at home. British workers needed their pro-imperialist prejudices challenged. Militant refused to do that, writing: “Thatcher and the Tory Government did not seek a conflict with the Bonapartist military-police dictatorship.”

Elections were their answer to the war: “We must demand a general election now, as a way of bringing down the Tories and returning the Labour Party to power with a socialist programme… If necessary, British workers and the Marxists will be willing to wage a war against the Argentine Junta.” Get the Labour Party to sit on top of the monster British imperialist state and then wage war against Argentina in the name of socialism! They were as bad on the North. Withdrawing British troops would lead to a bloodbath: “A common feature to what happened in Bosnia and Lebanon was that the central state collapsed… Ethnically based armed militias fighting for territory filled the vacuum of central authority in both cases. In Northern Ireland the state, especially since 1969, is the British state.” The soldiers responsible for Bloody Sunday were there to stop worse atrocities being enacted by the IRA? Not only did they conflate both sides of the sectarian divide, equating the violence of those trying to escape oppression and those defending it, but they also were suggesting it was a good thing the British troops were there!

In the mid-1980s Militant had a majority on Liverpool council but ended up implementing rate hikes when threatened by Thatcher’s government. PBP makes similar calls these days about running councils with the rest of the left, as if Sinn Féin, Labour, the Greens and the bureaucracy of the council could be convinced to lead Dublin City Council in a fight against the central state. Militant should have let Thatcher pull the council down and then called mass strikes and protests against this undemocratic move.

The Socialist Party in Ireland was evicted from the Labour Party in 1989 and changed their name from MIlitant Labour to the Socialist Party in 1996. They’d been a faction inside Labour since 1972. They had control over Labour Youth for a while in the 1980s and have been involved in many key working class campaigns over the years, particularly in the wake of the bank bailout of 2008. Their politics was very similar to that of their British parent organisation. They often fudged the issue of the state, were awful on imperialism and used the transitional method as a master key to justify almost anything.

During the United Left Alliance they correctly argued for the alliance to adopt a socialist programme and were strongly opposed by the SWN on this but when the household charges and water movements rose they adopted the PBP model by setting up the Anti-Austerity Alliance. Eventually they realised they couldn’t wear two hats and build the SP and a wider looser group at the same time and dropped the AAA. They were often more politically cohesive than the SWN/PBP - as even a transitional programme is better than none - and were generally more successful in elections until recent years when PBP has overtaken them as the main electoral vehicle on the socialist left. Recently the Socialist Party has leaned into identity politics. They regularly call protests against the “Manosphere” through their campaigning front organization ROSA.

They also have members who are key organisers in the Unite union, playing a key role in several workers’ struggles. But this work is disconnected from the identity politics activism of the party. In the North they’ve occasionally had decisive influence over some unions but never used this to call rank and file struggle. Paul Murphy’s RISE split from them after their international split over questions like class versus identity, the united front and, here in Ireland, how to categorise and relate to Sinn Féin and their support base. RISE joined PBP and tended to recruit on the basis of abstract left moralism and an obsession with telling the public they’d join a left government if it was willing to “rupture” with capitalism.

Tailism means being pulled by various social forces, the backward workers, the middle class, social movements. Tailism can shape contradictory and eclectic political positions - for example, PBP tail the Sinn Féin support base by offering themselves as governmental partners and can at the same time tail the moralism of the middle class on social issues. In PBP this tailism is shaped by their programmatic nihilism and their version of Trotsky’s “self-activity of the proletariat” - they constantly emphasise listening to the people. But they apply this inconsistently. Their left government position is shaped by the fact that saying you’ll enter government is popular. Yet their position on racism is shaped by having to be seen to take a stand no matter what. There’s nothing wrong with honesty but why throw it out in one case and keep it as a principle in the other? You should be honest in both instances.

This only makes sense if you understand that when it comes to the working class they argue that you can’t talk about revolution on the doors, in the estates. They’re cautious and conservative and tail their perception of where the middle ground is. But when they’re recruiting from and tailing middle class layers, where social issues are to the fore they have to be seen to be radical on those issues. This dynamic is evident across the left where softer parties like Labour disguise their retreat on class issues with posturing on social issues. That’s not to say that good working class people aren’t anti-racist, the good people are out there but it’s on class issues they can begin to lead the confused middle ground and win authority with which they can inoculate workers against division and isolate the far right.

Despite their supposed transitional programme framework the Socialist Party ended up in the same place as PBP. They may be more open about criticism of Sinn Féin but their election material has been very similar. But tailism can produce opposite results - the SP are terrible on imperialism and SWN are better. The SP captured positions on trade union bureaucracies in the North and so tailed an atmosphere that pandered to Orange prejudices. The SWN are predominantly based in West Belfast and Derry and so have traditionally had a better position on questions of war and imperialism.

The transitional programme relies on the objective situation creating a crisis that then allows mere reformist demands to automatically progress workers to revolutionary conclusions. This is basically the same as the PBP position. The programmatic nihilists and the programmatic formalists have arrived at the same positions because both positions rely on the spontaneous evolution of class consciousness through mere struggle in a coming apocalyptic scenario. For us Reds socialists need to be embedded in every struggle of our class in order to openly and honestly call for a revolution against capitalism.

Every door we knock on, every campaign we’re involved in, every flyer we distribute, if we keep repeating the argument for revolution we can normalise it. Revolution does require a crisis but it also requires a minority who know how to respond to that crisis. Without a class conscious minority, prepared ahead of the crisis and trained through struggle and through open advocacy of revolutionary politics, every such crisis will be co-opted by those who will lead movements back into coalescence with the state, or worse into the hands of reactionaries.

PBP are offering themselves as future governmental partners to Sinn Féin (while behind the scenes promising to talk out of talks), the SP are busy with identity based movements, while the RCI recruit students with stalls outside colleges and engage in ultra-left rhetoric. They’re all recruiting from the same kind of pool of college based activists. What we need is not just a differentiation from these political forms but a differentiation of content - we need to focus on building up workers.

What we need is a working class revolutionary party that is rooted in all the struggles of our class but is honest about what it will take to actually end capitalism. That’s what the Red Network is trying to build. We’re very small but with your help we can change that. We have no other choice. We have to rebuild a working class revolutionary tradition in Ireland and Trotskyism will clearly offer nothing but another dead end.

RED NETWORK

RED NETWORK