1926 to 2026: 100 Years Of Fianna Fáil

5 January 2026

When Eamonn DeValera led Fianna Fáil into the Dáil after the June 1927 election the newly elected Fianna Fáil TDs had revolvers in their pockets. They seemed like radical gunslingers, the smell of gunsmoke still on their jackets. DeValera had broken with Sinn Féin to form Fianna Fáil and make his way back to parliamentary politics. The new party had an aura of radicalism, helped by a panicked establishment press which tried to paint Dev and his gunmen as ‘communists’ and ‘Bolsheviks’ - but they were no such thing.

DeValera would soon own some of the most influential newspapers in Ireland, and in the 1930s he sat down with Archbishop McQuaid to write a conservative constitution, which was adopted in 1937. Soon Fianna Fáil were the establishment - the party to court with a brown envelope stuffed with cash if you wanted land rezoned or to get your hands on taxpayer cash to fund your new business.

Between them the two right wing parties, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, ruled the roost for decades. Political debate was suffocating, a charade of choosing between one right wing set of policies or another. It seemed like this right wing consensus could never be broken. We were trapped in an endlessly repeating cycle of Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael.

The 2020 election in Ireland was truly historic. There was a tidal wave vote for change. In the working class areas there was a huge vote for Sinn Féin and a significant vote for the radical left. Even Sinn Féin were shocked at the level of support they got - they hadn’t run enough candidates to scoop up all the potential votes. People were sick to death of the two-party system, exchanging Fianna Fáil for Fine Gael or vice versa.

The election opened up the possibility of Ireland’s first “left government”. “Vote left, transfer left” became a key slogan of the election and this was evident in the extent of Sinn Féin transfers that went to the radical left. But all that hope was dashed when the Green Party went into coalition with the two main right wing parties, Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil, who had dominated Irish politics since the foundation of the state. People were frustrated and furious. Since then the establishment has been able to use immigration as a wedge issue to chip away at Sinn Féin support.

The recent Presidential election again showed a strong vote for change. But why has Ireland been a two-party state for a century?

Fianna Fáil was founded by Eamonn DeValera in 1926 and he led them into the Dáil in 1927. DeValera had led the anti-treaty IRA but wanted to get back into mainstream political life. The new party tried to present itself as a ‘national movement’ - open to all classes. DeValera was careful to court workers, and stole the thunder of the weak Labour Party.

The Fianna Fáil economic policy was ‘protectionist’ - they were for building up native industry behind a wall of protective trade tariffs. This differentiated them from Cumann na nGaedheal who wanted to maintain trade links with Britain. With the union leaders and Labour Party reluctant to challenge Irish capitalism, Fianna Fáil were able to convince workers that protectionism would offer more jobs and a better economy.

When Fianna Fáil spoke out against capitalism it was always British capitalism that was the problem, not our own Irish bosses. They were able to capture working class anger after the global crash of 1929 and focus it within this nationalist framework. When unemployment rose - it was the British! When poverty rose - it was the British! It certainly was the case that the legacy of Imperialism had retarded the Irish economy, but it was also the case that we had our own layer of elite exploiters.

In most countries in Europe there is a clear left/right divide. There are right wing parties like the British Tories, who represent the wealthiest capitalists and landlords, and there are Social Democratic or Labour parties who are supposed to represent the working class, but fail to. So in Britain the Labour Party had thousands of working class organisations affiliated to it - it was seen as the natural political home for workers.

In Ireland the legacy of the Empire meant that nationalist freedom fighters were able to capture working class support for Irish capitalism. Irish workers weren’t just duped, they were promised economic advances by Fianna Fáil and genuinely believed their anti-British rhetoric. After all, 800 years of cruel British oppression, with the partition of the country leaving a chunk in the hands of Imperialism, meant there was a progressive or anti-Imperial side to the nationalism of Irish workers.

But it was being used by a ruling class faction to get workers to support their own local exploiters. Fianna Fáil’s protectionist economic policy was giving voice to the needs of a whole class of small factory owners who couldn’t compete on the open market with the larger and more established British companies. And they successfully wed workers to this capitalist led ‘national movement’.

In the 1932 election Fianna Fáil won enough seats to form a government, with support from the Labour Party. Cumann na nGaedheal helped Fianna Fáil appear more radical than they were by stirring up a red scare and insinuating that DeValera was getting his orders from Communists in Russia. Fianna Fáil became the political home for many Dublin workers who were unimpressed with the Labour Party.

Once in power Fianna Fáil took some progressive measures - like ending land annuity payments to the British. They also established many Irish state companies like Aer Lingus and Bord na Móna. But driving the Irish state machine required utilising the power of the Church to keep workers in line. DeValera understood this, and despite being excommunicated for opposing the treaty, he courted the Church hierarchy eventually working with the bishops to write the 1937 constitution.

They balanced strengthening the counter revolutionary state with throwing crumbs to workers to keep them on board. They introduced the right to collective bargaining for workers at the same time as banning women from many industries, effectively dividing the working class. Elite opposition to Fianna Fáil still existed in the form of the far right Blueshirt movement, led by ex-Garda commissioner Eoin O’Duffy. The union leaders used the rise of the Blueshirts to justify jumping into bed with Fianna Fáil.

The Blueshirt movement was never a real threat to state power and the union leaders had no interest in fighting Fianna Fáil or exposing the true nature of the Irish state. The middle class forces that traditionally roll in behind far right movements were happy enough with the direction Fianna Fáil were taking and weren’t attracted to the fascist path.

When the economy was doing well Fianna Fáil built housing estates, further winning over workers’ support. They built 132,000 new houses between 1932-1942. The contracts for state house building helped to establish some of the biggest irish companies – such as Cement Roadstone. They were able to buy off workers and bosses.

When the economy did badly they wrapped themselves in the tricolour and turned to the Church to “humble” the people. The party said it stood for the “common man” but that common man could be a wealthy merchant or a rich builder, as well as a worker or small farmer. Fianna Fáil tried to be all things to all people in public, while behind the scenes they became the A-team of Irish capitalism.

The government decided to keep Ireland out of the war with Hitler, declaring the “Emergency”. They considered banning strikes but decided against it in order to keep the union leaders in their pockets. They used concerted “red scares” to split the trade union movement in 1944. There was huge class anger after the war, with a rise in strikes and protests including big strikes by ESB and bus workers.

When the First Inter-Party government came to power in 1948 they broke a 16 year-long stint in power for Fianna Fáil. This new coalition government was made up of Fine Gael, Labour, National Labour, Clann na Poblachta and Clann na Talmhan. When Noel Browne proposed the Mother and Child scheme - providing basic healthcare for working class families - he was forced to quit. Even the Labour Party said they wouldn’t go against the Bishops.

Every time Labour had an opportunity to win workers away from Fianna Fáil they blew it. Fianna Fáil were able to win back 61,000 voters and return to power. They were then able to steal the Labour Party’s thunder by introducing a Welfare Act and a Health Act that included a version of the free Mother and Child scheme. But the 1950s saw the Irish economy falter and Fianna Fáil’s deflationary budget just made the situation worse.

There was a huge post-war boom across the Western world and by opening up the economy to this already expanding market Fianna Fáil could claim the rising Irish economy was their doing, it wasn’t. All they did was benefit from an expanding post-war global economy. The rise in employment in the 1960s saw workers’ confidence rise and there were growing numbers of strikes. Fianna Fáil tried to maintain a close relationship with the union leaders to curb this growing rank-and-file militancy. In return for policing the working class the union bureaucracy were given a greater role in national policy.

As international corporations entered the economy the multinationals demanded an educated workforce, leading to the introduction of free secondary education. Leading Irish capitalists decided to unite and argue for their class to come in behind Fianna Fáil, forming an organisation of leading industrialists called ‘Taca’. ‘Taca’ was derived from the Gaelic word for ‘support’ or ‘help’ - ’tacaíocht’. The bosses ‘helped’ themselves to political influence, while the Fianna Fáil politicians ‘helped’ themselves to piles of money. These were the much-talked-about “men in mohair suits”.

As author Rosita Sweetman wrote in 1972:

“You may wonder why the Fianna Fail government doesn’t do something about controlling the price of land, the building of houses and general accommodation problems in a city bursting at the seams. …If you are still sceptical, you might take a trip around the newer, posher estates being built on the outskirts of Dublin. The names Gallagher, McInerny and Sisk will re-occur constantly on the billboards. Now, if you dig a little deeper you will discover that Mr. Matt Gallagher and his brother are two of the biggest building/contractors in Dublin and they’re among the biggest contributors to TACA. And TACA is the fund-raising section of the Fianna Fáil party - without TACA, Fianna Fáil would go bankrupt in the morning. And if you still don’t see why the government don’t do something about compulsory purchase of land for subsidised housing, and curbing the activities of the private speculators, you’re very naive indeed.”

Some things never change, eh? Eventually, the word ‘TACA’ became a ‘dirty’ word, and ‘Tacateer’ was coined to describe those who went to such dinners and regularly had their pictures taken with Fianna Fáil Ministers.

In the late 1960s working class militancy led to a massive rise in support for the Labour Party, but they blew it and went in with Fine Gael in 1973. Everytime the conservative consensus could be broken Labour bottled it and capitulated to the right wing. With Fine Gael and Labour implementing cuts Fianna Fáil were able to surge back into power with one of their highest votes ever.

They promised the abolition of rates on houses, the abolition of car tax and the promise of reducing unemployment to under 100,000. Fianna Fáil adopted an American-style campaign - with loudspeakers in every town, and regular rallies. The Fianna Fáil party alone got 50.63% of all first preference votes and 56.76% of Dáil seats. The two right wing parties, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, had over 80% of all votes, with Labour on 11.63%.

When people spoke of the inherent conservatism of the Irish worker they were forgetting that only a decade previous papers like the Irish Times were frustrated that:

“Our established system of manager-worker relations is showing cracks, and one can imagine, in the spirit of the old-time joker, that an eccentric has only to paint a slogan on a placard, to march up and down outside any major establishment in order to throw a whole industry into chaos with the magic words Strike On Here”.

Fianna Fáil began their new stint in power with a turn toward industrial development - but they wanted the working class to cough up the extra tax cash necessary to fund it. This provoked the massive Pay As You Earn protest movement. They were forced to retreat by people power.

While Thatcher launched an attack on the trade unions in Britain in the 1980s - Charlie Haughey was able to begin the process of introducing Irish neoliberalism with the unions in tow. Haughey signed a ‘Programme for National Recovery’ with the union leaders accepting wage restraint and public sector job losses. It was to the sound of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union band playing ‘A Nation Once Again’ that Haughey took the stage at his first Ard Fheis as party leader.

Charlie Haughey criticised Thatcher’s privatisation programme - keeping the unions in his pocket until his political successors started handing over state assets to private capitalists a decade after the ‘Programme for National Recovery’ was signed. Haughey ruled like a medieval tyrant. In December 1982 an Irish Times reporter shocked the country with revelations of phone tapping of journalists by the Fianna Fáil government. Vincent Browne was among those spied on by the government. Their phones had been tapped officially with warrants signed by Fianna Fáil Minister for Justice Sean Doherty. The whole thing had been approved in discussions with Deputy Garda Commissioner Joseph Ainsworth. Doherty admitted the transcripts were shown to Charles Haughey, which led to Haughey standing down as Taoiseach.

Haughey was born in Mayo in 1925, but the family moved to Donnycarney in Dublin. He studied commerce at UCD before qualifying as a chartered accountant and then entering politics in 1957 when he stood for the Dáil. He immediately became part of a circle of “men in mohair suits” - “By day he impressed the Dáil. By night he basked in the admiration of a fashionable audience in the Russell Hotel. There, or in Dublin’s more expensive restaurants, the company included artists, musicians and entertainers, professionals, builders and business people. His companions, Lenihan and O’Malley, took mischievous delight in entertaining the Russell with tales of the Old Guard. O’Malley in turn entertained the company in Limerick’s Brazen Head or Cruise’s Hotel with accounts of the crowd in the Russell. On the wings of such tales Haughey’s reputation spread.”

He became Minister for Justice in 1961 and Minister for Agriculture in 1964. He used the Offences Against the State Act to jail protesting farmers in April 1966.

Despite previously taking a hard line on the IRA Haughey was caught up in the so-called ‘arms crisis’ in 1970. Haughey and Neil Blaney were part of an official government sub-committee set up to look after refugees from the North in the wake of vicious attacks on Catholics in Derry and Belfast. When Blaney took a hard line on the North and called for intervention, including military intervention to protect Catholics, Haughey couldn’t allow himself to be outdone - after all Blaney was a rival candidate for the leadership of Fianna Fáil. From previously being opposed to physical force Republicanism Haughey suddenly wrapped himself in the tricolour.

In October 1969 Irish Army intelligence met with the Northern Citizen Defence Committees in Cavan. Those present included IRA officers. Blaney and Haughey were alleged to have made plans to ship arms through Europe using contact with a former Nazi. Haughey dismissed a meeting with IRA Chief of Staff Cathal Goulding as a “chance encounter”. The Garda Special Branch informed the government and the opposition, leading to Blaney and Haughey getting the sack. In May 1970 they were put on trial but all charges were dropped. It did Haughey no harm and increased his reputation with poorer working class people - a reputation he’d use to get close to workers, and like any good mafia don - get you close, just to stab you in the back.

On the 11th of December 1979 Charles Haughey ascended the throne as leader of Fianna Fáil. One of his first actions was to get in touch with advertising firm Saatchi & Saatchi - the Iraqi-led firm had come up with the “Labour’s not workers” tagline for Margaret Thatcher and the Tories. Her attack on the working class was dressed up in buzzwords like “prosperity”, “freedom”, “choice” and “opportunity”. Destruction of the welfare state was dressed up as rolling back the “frontiers of government”.

Haughey told them he “wanted a new image”. The country was sinking into an economic depression when Haughey became Taoiseach. He took over national TV to put on his best fake sincerity and inform the country we were “living beyond our means”. The man bought himself an island and was telling poor people they had to tighten their belts. Days before taking office Allied Irish Banks forgave Haughey £400,000 of a £1 million debt. He had warned the bank that “I can be a very troublesome adversary”.

After a short-lived Fine Gael administration Fianna Fáil were back in power in 1982 with Haughey at the wheel. Haughey was able to keep a weakened Fianna Fáil in power with the support of Workers Party TDs and by buying off Independent TD Tony Gregory. The government offered inner city Dublin £100 million in investment and in return Gregory would keep Fianna Fáil in power to ruin the lives of working class people in every other constituency. It was a rotten deal. Gregory withdrew his support when Haughey introduced spending cuts.

This government also introduced the phrase “GUBU” into Irish politics - a phrase meaning a scandal. In July 1982 a 27 year-old nurse, and a farmer, were murdered by Malcolm Edward MacArthur who after committing these terrible crimes went and attended a match at Croke Park with the Attorney General Patrick Connolly. The murderer was eventually arrested at Connolly’s home. Haughey described the events as “a bizarre happening, an unprecedented situation, a grotesque situation, an almost unbelievable mischance.” The phrase “grotesque, unbelievable, bizarre and unprecedented” was shortened to GUBU. Haughey’s final stint as Taoiseach from 1987 to 1992 ended with his resignation over the phone-tapping scandals.

Fianna Fáil introduced regressive anti-union legislation to hold workers down. The 1990 Industrial Relations Act, introduced by then Minister for Labour Bertie Ahern, saw Fianna Fáil place historic limitations on the Irish trade unions. Fianna Fáil had introduced a Trade Union Bill in 1941 that made negotiating licences obligatory for unions and established a tribunal which could give exclusive negotiating rights to unions in any employment. In 1966 they introduced another Trade Union Bill which was heavily criticised by the unions.

The new bill regulated strikes - a clear majority vote was needed before unions could take action. Opposition to the bill from the union leaders led to its withdrawal - the late 1960s was a period of intense class struggle. But once rank-and-file militancy waned, the unions leaders raised the white flag and negotiated a pay deal and allowed the passing of a new Trade Union Act in 1971. The new act changed the rules on negotiating licences and deposits and in 1975 the Labour Party’s Michael O’Leary introduced a Bill which encouraged amalgamations of unions.

Fianna Fáil had returned to power in 1977 and set up a “Commission of Inquiry on Industrial Relations” but it took them a few years to sew up an arrangement with the union leaders. The 1987 Programme for National Recovery stated that “The Minister for Labour will hold discussions with the Social Partners about changes in industrial relations”.

When Bertie Ahern made industrial relations proposals in 1989 the union leaders sang his praises: “….if it worked properly it would make a positive contribution to the development of good industrial relations in Ireland”. With a few changes here and there this became the regressive 1990 Act. The union leaders were co-operating with Fianna Fáil to tie up the working class hand and foot. The new act would repeal the 1906 British regulations for Irish unions - but then repackage them, with worse outcomes for workers. The whole Act was written from the employer’s perspective.

It ruled out taking action over ‘individual’ grievances unless the worker making the complaint had spent months fighting through the Employment Appeals Tribunal. This meant that a worker sacked for union organising couldn’t be reinstated through strike action, as such action was illegal. The union leaders had abandoned “an injury to one is an injury to all” - effectively outlawing solidarity!

The 1990 Act also changed the nature of pickets. It was lawful for workers “…acting on their own behalf or on behalf of a trade union…..to picket…..a place where their employer works or carries on business….. " but it was illegal to ask members of the same union to come out in solidarity at other workplaces or to join a small workforce maintaining pickets at a small workplace like a shop. This meant that mass solidarity pickets were now also illegal. The 1906 act made no distinction between primary and secondary pickets, but the Fianna Fáil Act changed that. Section 11(2) permitted secondary picketing “…..if, but only if, it is reasonable for those who are so attending to believe…. that that employer has directly assisted their employer….for the purpose of frustrating the strike….” This was a ban on secondary pickets because it was impossible for workers to legally prove that another employer had “frustrated” their strike and given direct assistance to their own employer. The union leaders used this as an excuse to encourage workers to pass picket lines, eroding the age-old respect for pickets that had been ingrained in the Irish working class.

ICTU said: “The mere fact that employees of another company are passing the picket line in order to carry out work for the employer in dispute would not in itself leave that company open to secondary picketing.” So much for real pickets.

Thousands of workers who worked on contracts, for example in catering, suddenly found themselves banned from picketing their workplaces because it wasn’t the primary address of their particular employer. Picketing the college or school where they cleaned or worked serving food would now be ‘secondary’ picketing and illegal.

The legislation also defended scabs: “…the trade, business or employment of some other person, or with the right of some other person to dispose of his capital or his labour as he wills”. So a picket that stopped a scab was now illegal. But then what was the point of a picket? The picket was hollowed out and made a token show of protest while the real work happened at the top in negotiations between the boss, the union leaders and the government. It was still possible for unions to organise a ballot to black goods from a workplace involved in a dispute. But they wouldn’t use it unless pressured by workers from below.

As teacher and trade unionist Gregor Kerr explained:

“Fianna Fail had chosen the path of ‘social partnership’ to tame the unions. They decided not to follow Thatcher’s example of declaring war. Instead, through involving them in the ‘decision-making process’, they very cleverly got the ICTU leadership to agree to voluntarily disarm its membership. Union leaders were prepared to go to any lengths in order to maintain their supposed position of influence.”

Fianna Fáil split with the right wing Progressive Democrats which had formed around personalities such as Des O’Malley and Mary Harney. Fianna Fáil returned to government in 1987 shouting about Fine Gael cutbacks. The campaign produced the famous Fianna Fáil slogan that cuts in health spending affect the “old, the sick and the handicapped” - but as soon as they got in they cut back on hospital wards.

Instead of exposing the hypocrisy of Fianna Fáil the Fine Gael opposition proposed the “Tallaght Strategy” where they would let Fianna Fáil cuts pass unopposed in the Dáil. The Haughey years led to a rake of tribunals, but the party survived. When Albert Reynolds took over at the helm of Fianna Fáil the economy was in such a desperate state they turned to the Labour Party to form a coalition. Reynolds was a key figure on the showband music scene. He became very wealthy from the music scene during the 1960s and invested in a number of businesses including a pet food company, a bacon factory, a fish-exporting operation and a hire purchase company. He was a capitalist business owner. Being a businessman looking for a political home he stood for Fianna Fáil in 1977. He was later rewarded for loyalty to Haughey with Ministerial posts in the 1980s. With Haughey gone, people expected change in Fianna Fáil.

But the days of scandal continued. In June 1994, with strain showing between Fianna Fáil and Labour, it emerged that the Reynolds’s family pet food firm had benefited from a £1 million investment made under the “passports for sale” scheme. The money came from a rich Saudi family called Masri - in return they bought themselves Irish citizenship. Fianna Fáil could always be counted on to sell off the family silver if it benefited them or their business mates.

Fianna Fáil and Labour were arguing in September 1994 when Labour leader Dick Spring was in Tokyo. Reynolds proposed at a Cabinet meeting that Attorney General Harry Whelehan be appointed High Court President that day. A Labour threat to walk out postponed the decision. Worried Labour backbenchers urged their leaders to stick with the government.

In October 1994 it emerged that a request for the extradition of the Norbertine Order paedophile priest, Brendan Smyth, had been in the office of the Attorney General for seven months. It had been received by the Gardai on April 23rd, 1993. A month later it was referred to the Attorney General’s office. There it remained until Smyth decided to return voluntarily to Northern Ireland. There was a huge public uproar. Reynolds stuck to his guns and demanded the appointment of Whelehan to the High Court position immediately. Labour threatened to walk out unless Reynolds apologised.

But his Dáil speech didn’t even contain the word ‘apologise’. The government fell, and Fianna Fáil appointed a new leader, a man described by Haughey as “the most devious and most cunning!” Bertie Ahern had been a Haughey sidekick for years, a man deeply embedded in Ireland’s elite, but who spoke with a working class accent. This was typical Fianna Fáil - a party of elite gangsters who pretended to be everyone’s friend. Fianna Fáil and the Progressive Democrats formed a government in 1997 and again in 2002.

Bertie Ahern claimed that Fianna Fáil were responsible for the rise of the Celtic Tiger. The government called for wage restraint and made Ireland a destination for corporate funds. In 1985 wages accounted for almost 75% of Ireland’s GDP. In 1998 this had fallen to under 60%, compared to just under 70% on average in Europe. As the share of the economy going to wages fell, people were encouraged to take on an ever-growing debt burden.

When investment in manufacturing fell in 2001 Fianna Fáil encouraged a speculative property and financial bubble. It wasn’t based on real economic activity. That whole economic set-up was as fragile as a house of cards. Ireland was ranked the second wealthiest OECD economy behind Japan and ahead of the UK, US, Italy, France, Germany and Canada. But while there were 30,000 millionaires at the top, many workers were stressed and stretched by rising rents, overwork and debt. Fianna Fáil just encouraged the orgy at the top while shouting down those who said it was all unsustainable. To sustain the boom, the Irish banks borrowed about €450 billion from European banks. That was three times the size of the whole Irish economy.

Ahern was exposed by the Mahon Tribunal as having signed ‘blank cheques’ for Haughey when Ahern was Minister for Finance. He was also shown to have taken payments from developers in the 1990s. Fianna Fáil were returned to power in the 2007 election in coalition with the Progressive Democrats and the Green Party. The government wouldn’t be in power long before the speculative greed of the boom years led to a massive economic collapse, worsened by the global economic collapse - which had at its heart the same kind of mad policies.

Ahern turned on the people and blamed them for the boom and bust:

“cynics and knockers, people who always see the glass as half empty. I can’t understand people who are always bitching, saying ‘It’s the Government’s fault, it’s the doctor’s fault, it’s the cat’s fault.’ It’s everybody’s fault except their own.”

The close connections between Fianna Fáil and the developers had seen the Irish developers borrow billions through banks like Anglo Irish. Now that the bill had to be paid for all that gambling, Fianna Fáil turned on the working class with ferocity.

Fianna Fáil were at the heart of the network of developers connected to Anglo Irish Bank. Former Anglo chief executive Sean Fitzpatrick also sat on the board of the Dublin Docklands Development Authority (DDDA) while Anglo Irish Bank was providing loans to the DDDA. Fianna Fáil’s Noel Dempsey appointed Fitzpatrick to the DDDA in 1998 - Dempsey was the Minister for the Environment and Local Government at the time. Another Fianna Fáil Minister Séamus Brennan appointed Fitzpatrick to a non-executive role at Aer Lingus. Fitzpatrick secretly borrowed €100 million from Anglo Irish Bank, hiding this from auditors for almost a decade. The Irish banks had thrown money at property speculators all through the Tiger and by May 2008 were completely broke.

People like Sean Fitzpatrick and other leading bankers lobbied the Fianna Fáil government for a bailout. Financier Dermot Desmond joined with Davy Stockbrokers in begging the government to give the banks a massive handout. On July 28th, 2008, Fianna Fáil leader Brian Cowen played golf and had dinner with Anglo’s chairman, Seán Fitzpatrick. The notion that they didn’t discuss the bailout is ludicrous. The bankers had access to the top Fianna Fáil politicians. Pat Farrell, the general secretary of Fianna Fáil from 1991 to 1997, went on to be chief executive of the Irish Banking Federation before landing a top job at Bank of Ireland.

In early September, financier Dermot Desmond picked up the phone and rang the Central Bank governor John Hurley about a bank guarantee and said: “Look, I’m in this market, I see things happening. I think you might need to consider this guarantee thing.”

In other words - “We the 1% need you to screw over the taxpayers and look after our cash!” As the Irish economy collapsed Fianna Fáil decided to have a party - they called a special “think-in” at the Clayton Hotel in Galway. As they were lowering back pints the US giant Lehman Brothers collapsed leading to further panic on global markets. When RTÉ’s Joe Duffy show had hundreds of people ring in in panic about the banks, Cowen rang the head of RTÉ to tell him to stop broadcasting bad news that might cause a run on the banks.

On Saturday Sept 20th 2008 Fianna Fáil guaranteed all banking deposits up to €100,000. By September 2010 Fianna Fail had put €50 billion into the banks and set up NAMA to take on the bad loans of the developers.

Brian Lenihan had received a warning from ECB President Jean-Claude Trichet telling him to ‘save’ Irish banks. Lenihan said: “Mr Trichet rang me, and hadn’t been able to get through to me. I was at a racecourse in County Kilkenny at a Fianna Fáil event on the Saturday.”

The ECB threatened to let off “an economic bomb” in Dublin if the government didn’t act. Not that Fianna Fáil needed to be strong-armed into taking action to save their banking and developer friends. The EU was on the lookout for French and German banks who had loaned billions to Anglo Irish. If the Irish taxpayer could be forced to put billions into the Irish banks, then the European banks could get their cash back. It was a bailout of the European banks at the expense of the Irish working class. While Ireland makes up only 0.9% of the population of Europe, thanks to Fianna Fáil we ended up paying for 42% of the cost of the European banking crisis. By 2013 every single man, woman and child in Ireland had paid €9,000 for the bailout.

The austerity policies Fianna Fáil subsequently pursued broke apart their national movement - working class people could see them for the elite party that they always were. It was impossible for Fianna Fáil to reconcile policies that favoured the elite with crumbs for workers - when it came to it they’d take the last crumbs from the worker’s mouth to bail out their masters. Social welfare was slashed, public-sector pay was cut and new levies and taxes were imposed on working people. The Fianna Fáil vote collapsed in working class areas. They only got 20 seats nationally, down from 77 seats in the previous election.

Bertie Ahern had been replaced by Brian Cowen in 2008, but Cowen had overseen the transfer of billions into the banks and NAMA while bringing the IMF in to ‘bailout’ Ireland. His approval rating fell to just 8% - the lowest for any Irish leader. While the working class voters defected to the Labour Party, upper class voters swung from Fianna Fáil to the other right wing party, Fine Gael. Fianna Fáil were viewed as too toxic to even be considered for coalition with the other parties.

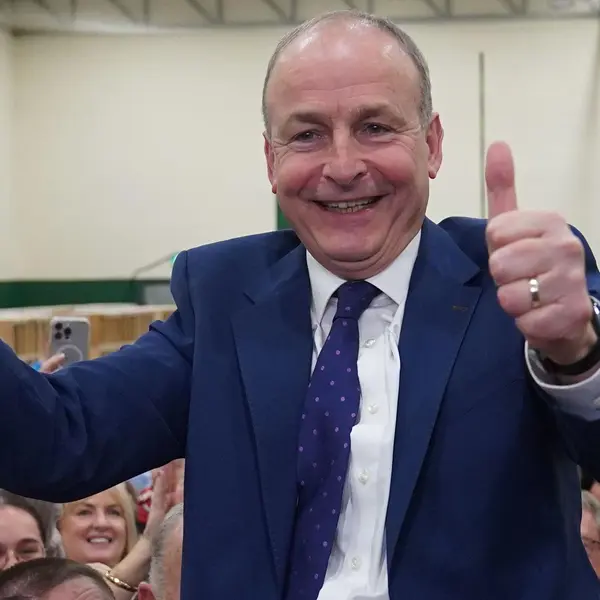

When Micheál Martin took over as Fianna Fáil leader he promised ‘clean politics’ while trying to distance himself from the ‘ghosts of Fianna Fáil’ - which was a bit rich coming from a man who had taken cash from developers. Micheál Martin’s Holiday Home in Courtmacsherry was built by Fianna Fáil donor, John Fleming. When he was called before the Mahon Tribunal’s investigation into the corrupt Quarryvale development, his memory got fuzzy. The Tribunal was investigating an allegation by Tom Gilmartin that developer Owen O’Callaghan had told him that he had “given a five-figure sum to Micheál Martin”. O’Callaghan first told the Tribunal that a payment of £5,000 he gave Martin in 1991 was for the ‘Atlantic Pond Restoration Fund’ but he later changed his evidence to say that it was “a political contribution to Micheál Martin for the June 1991 local elections”.

Martin said he had no memory of a meeting with infamous lobbyist Frank Dunlop in November 1991, which had been recorded in Dunlop’s diary. He said he’d never brought O’Callaghan to meet Bertie Ahern, but when confronted with clear evidence that the meeting was recorded in Ahern’s ministerial diary Martin just said he couldn’t remember. He also somehow never saw anything dodgy going on in all his years around Haughey and Ahern.

The Department of Health, for which Micheál Martin had been responsible when he was Minister for Health, had illegally taken €2 billion in charges from elderly residents of nursing homes. He had been told about it, but later claimed he didn’t know. He clearly had real problems with his memory. The continuation of austerity by the Fine Gael/Labour government saw some voters, especially in older demographics, return to Fianna Fáil. But they were incredibly weakened. The party’s percentage of the vote went from 17.5% in 2011 to 24.3% in 2016.

But 24.3 % was still the second lowest percentage they had ever got and a very long way from the close to 50% of votes they could get at the start of the 1980s. The party had called for water charges, but sensing the power of the huge mass movement against the charges, had reversed their position. Fianna Fáil could always be relied on to be unreliable opportunists. Despite increasing their seat numbers it was still the second worst election for the party in its history. They weren’t able to claw back support in the Dublin working class - in Dublin Central they’d held two seats from 1997 to 2011.

People were sick to death of the old politics and the establishment knew it. They stood younger candidates, although they were often drawn from political dynasties vying to take daddy’s seat. But they also realised they had to embrace progress in the form of social issues like marriage equality and repeal. The austerity years had weakened the establishment and they needed to win back voters. But this limited embracing of progressive issues saw Fianna Fáil frustrate many of its conservative Catholic supporters, especially in rural areas.

When Micheál Martin realised the tactical necessity of hitching Fianna Fáil to the movement to repeal the 8th Amendment it provoked a revolt inside Fianna Fáil. A majority of the party’s TDs lined up with the conservative Catholic ‘No’ campaign. In May 2018 31 posed for a photo shoot in Dublin while holding ‘No’ placards. At the party’s Ard Fheis the previous October, delegates had approved a motion to save the 8th Amendment by a margin of three to one. The Fianna Fáil leadership was worried about conforming to the old saying that they were “male, stale and beyond the Pale”.

The party’s founder Eamon de Valera famously said that whenever he wanted to know what the Irish people thought, he simply looked into his own heart and immediately knew the answer. But with austerity having exposed the class affiliation of Fianna Fáil - to the bankers and developers - now repeal was exposing just how socially conservative their base was. They were very far from having a finger on the ‘pulse’ of the Irish people.

But the many-headed snake of Fianna Fáil is very hard to root out of Irish life - they are deeply embedded in networks of businessmen and developers, of publicans and landlords. It’s that social base that helps to restore them to life every time they falter. They have been wounded over the last decade but were still able to claw their way back into power after the 2020 election. When the Fine Gael government was weakened by the resignations, Fianna Fáil stepped in with a ‘confidence and supply’ agreement.

They would pretend to be the opposition to Fine Gael while at the same time propping up the government and allowing Fine Gael budgets through the Dáil. It was a very Fianna Fáil arrangement. The two right-wing parties could unite to exclude the left while Fianna Fáil masqueraded as opposing Fine Gael. They wanted to have their cake and eat it too.

The ‘confidence and supply’ agreement paved the way for the coalition of the right that came after the 2020 election. Gone were the days when Fianna Fáil could just form a government without a coalition partner. Even Fine Gael were weakened. The combined vote for the two establishment parties, at 43%, was much lower than the vote for Fianna Fáil alone in 1977. Fianna Fáil had lost 7 seats in the election, while Fine Gael lost 12. The two right wing parties together were still short of the numbers to form a government, forcing them to form a coalition with the Green Party.

They would rotate the position of Taoiseach between Micheál Martin, Leo Varadkar and Eamon Ryan. They took power just as the covid pandemic swept across the world. Fine Gael’s Varadkar had been playing a caretaker role in the first phase of the virus, his poll ratings having increased as a result. In the initial phase of the virus even the boss’s club IBEC were for the health measures and so the caretaker government was given the green light by their masters to take the necessary health measures, including lockdown.

In the 2024 election Fianna Fáil won 38 seats, 22.2% of the vote. They’d won 10 extra seats. Their recovery was in part due to the success in making immigration a wedge issue which lost Sinn Féin 100,000 voters. Martin was back in the driving seat with support from Fine Gael and Indepedents led by corrupt TD Michael Lowry.

The fiasco of Fianna Fáil’s Presidential election campaign in 2025, where they stood former landlord Jim Gavin, saw calls for Martin to go. But it will take far more than one election gone wrong to clear out Fianna Fáil. They grow out of the soil of Irish life - they are the political expression of a particular class of Irish capitalists, landlords and developers and as long as those classes exist their political expression will exist.

Destroying the hold of Fianna Fáil over Irish political life won’t be as simple as voting in Sinn Féin, Labour and the Greens to replace them. Sure didn’t Fianna Fáil start with guns on holsters and promises of change? Those soft left parties will coalesce with the system and Fianna Fáil will be waiting in the wings to return to power. Of course, we need to vote Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael out - but we need to be realistic about how we actually transform Ireland.

It will take a working class rebellion to overturn not just the corrupt political state machinery Fianna Fáil have built over a century of misrule but to challenge the Irish bosses that Fianna Fáil represent, putting the wealth of the country under democratic working class control.

RED NETWORK

RED NETWORK